On one day in late March, Twitter followers curious about Syria, Yemen and Libya could find a tweeter who calls himself “Ian56” tweeting about all those topics and more. “Ian56” also had things to say about U.S foreign policy, the Manchester bombing and the Islamic State. The common denominator in nearly all the account’s tweets is the villain: the tweeter invariably targeted Western democratic governments, usually the U.S. and Britain.

“Ian56,” it seems, is not a real person. He (or she) does seem to be the creation of a flesh and blood Russian, experts say, not a “bot” but a “troll.”

Last November, “Ian56” turned up in a Polygraph.info fact check of an Italian journalist’s documentary which falsely alleged that Georgian mercenaries were responsible for sniper killings during Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan Revolution. The documentary was promoted by Russia’s state-funded Sputnik News agency, in an article which included some tweets on the subject by “Ian’s” Twitter account (@Ian56789).

“Ian56” is very interested in topics of great importance to the Kremlin, such as the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 (MH17) air disaster, the murder of Boris Nemtsov, and more recently, the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal in the southern English city of Salisbury. "He” tweets prolifically on these topics, always with a pro-Kremlin slant.

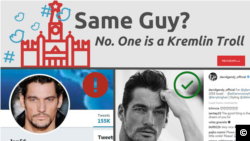

Perhaps most unusual is “Ian56’s” avatar, which is actually a photo of model David Gandy.

Ben Nimmo, the Senior Fellow for Information Defense at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, studies the exploits of “Ian56” and similar accounts on Twitter. His recent article in the online publication Medium profiles such fake pro-Kremlin accounts and demonstrates how they operate.

According to Nimmo, these accounts are “trolls” rather than bots.

“A bot is an automated account,” Nimmo said. “Ninety-nine percent of the time it will retweet and ‘like’ other people's posts. If it's arguing with you, there's a fair chance it's not a bot.”

Accounts like “Ian56” do engage with other accounts, but always with a pro-Kremlin narrative.

“It ticks all the right boxes,” said Nimmo. “It's posted what I would consider the Kremlin narrative on MH17, on Crimea, particularly importantly it posted a lot on Boris Nemtsov the day after he was assassinated.”

Several other experts on Russia’s online tactics agree with Nimmo’s analysis of “Ian56."

Alexandre Alaphilippe of EU DisinfoLab called “Ian56” a “multi-recidivist troll.” The DisinfoLab identified the account as being involved in specific troll “operations,” including promoting the Kremlin narrative that claims British intelligence is to blame for the nerve agent poisoning. Alaphillippe also points to the use of #SyriaHoax, a hash tag “campaign denying use of chemical weapons in Syria.” Alaphilippe said the account had been found promoting pro-Brexit narratives as well as disinformation about the Nice terrorist attacks.

“From our perspective, you have someone very involved and connected within close to Kremlin narrative networks,” Alaphilippe told Polygraph.

The EU DisinfoLab uses its own methodology, “a combination of powerful algorithms and human expertise” to analyze account’s keywords and locations but also "map their interactions, interests and relationship to other users.”

Damien Phillips, a London-based public affairs consultant with experience in studying disinformation tactics, is also convinced that “Ian56” is a fake account designed to spread a Kremlin narrative. He highlighted several features of the account’s activity which, in his opinion, makes it highly suspect. These include activities include what Phillips described as “the relentlessly pro-Russian government line throughout the posts,” the use of “whataboutism” by comparing the Skripal investigation to the U.S. claims about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and spreading conspiracy theories aimed exclusively at the U.S. and its allies.

“Throughout the tweets you can see numerous examples of what one commentator has referred to as a kind of "weaponized relativism,” Phillips explained.

“The underlying basis for a lot of the tweets is the idea that there are multiple interpretations of the truth and this is designed to confuse anyone trying to work out what actually happened.”

Among the most disturbing conclusions is DisInfoLab’s finding that “Ian56” is “an influencer for many extreme/radical activist networks (that) post death threats to elected people,” said Alaphilippe, who told Polygraph.info he could say no more publicly about that finding.

According to Nimmo, one way to discern if an account is real or not is to search for tweets on those key subjects where the Kremlin wants to push a specific narrative. But it is also important to note what is absent, such as innocuous tweets about non-political interests, or political tweets that are not related to Russia or pro-Kremlin narratives.

Inconsistencies in the personas’ claimed background and language are also clues. Nimmo notes, for example, how “Ian56”claims to be from Britain, yet also claimed to have voted for Ron Paul in the U.S. presidential election of 2012 (Paul, who had lost the Republican primaries that year, did not make it to the general election). “Ian56” later claimed that he was a British citizen planning to move to the U.S. in 2013, after that election he had supposedly voted in.

The account’s language is also inconsistent and unnatural. First there is the bio, which identifies “Ian56” as a “Politics Analyst.” The word “political” would sound more natural, and “analyst” shouldn’t be capitalized here. “Common Sense” is also unnaturally capitalized, unless it is a reference to Thomas Paine’s famous American Revolutionary War pamphlet by that name. That would certainly go with one’s interest in “the Bill of Rights,” but this is odd for a citizen of Britain, which the nascent colonies defeated two centuries ago. Ben Nimmo also noted that the account uses a mixture of British and American spelling; some words are consistently spelled in the British manner, while others are strictly American spelling.

Recently a new suspicious account has appeared on Twitter which may be linked to Russia’s pro-Kremlin trolling operation. “Kat O’Hara” (@KatOHara4), supposedly an ordinary Irish woman, joined Twitter in October of 2017. However, the account has only tweeted twice -- both of them occurring on March 27 and both on the subject of the Irish government’s decision to expel a Russian diplomat in solidarity with Britain over the Salisbury poisoning of a former Russian spy. No bio is given, and the account follows @RT_com, a Russian state news organization, and a number of “anti-establishment” figures whose message is often promoted by pro-Kremlin media.

The Twitter account @GorseFires, which advocates for Ukraine and calls himself “United against Russian aggression,” called out “Kat O’Hara” on Twitter as “a newly activated Russian FSB troll.”

“On the face of it, the account you flagged up is highly likely to be part of a disinformation campaign,” Phillips, the public affairs consultant and expert in disinformation tactics, told Polygraph.info.

In particular, he notes the deflection to another issue and the repetition of phrases in both of “Kat O’Hara’s” tweets.

“The big giveaway to me is the classic use of a deflecting narrative regarding the ‘homeless crisis’ to take attention away from the issue of Russian involvement in the poisoning and to muddy the waters of the whole issue,” said Phillips, referring to one of the account’s two tweets. Another telltale sign is “repetition of key phrases in both tweets such as ‘staged propaganda stunt,’” he added.

Alexey Kovalev, a veteran Russian journalist who created the fake-busting site Noodle Remover, has expressed doubts about “Kat O’Hara” being a troll account. According to him, the things to look for in a Russian troll account would be “furious activity, dozens or even hundreds of tweets every day.”

He says the timeline of such accounts “mostly consists of retweets of other similar accounts, no personal pics, tweets, etc., just incessant political tweets/retweets, and an unusual number of followers…:”

“Kat O’Hara” has tweeted only twice and has few followers.“Ian56” is a prolific tweeter. While he said the “Kat O’Hara” account was “definitely weird,” he wasn’t able to say for sure whether it was a bot or troll account.

Kovalev also suggested that accounts could be “hijacked” in order to put out Kremlin-friendly messaging. One such famous case was that of “Carlos,” a Twitter account which claimed to be a Spanish air traffic controller working at Boryspil International Airport in Ukraine. Shortly after the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 over Eastern Ukraine, the account began tweeting about seeing Ukrainian military planes flying near MH17 shortly before it disappeared from radar screens. Russian state and Kremlin-friendly media cited the Carlos story, and later it was claimed that Carlos had to leave Ukraine due to death threats. Ukrainian officials confirmed that no foreign air traffic controllers were employed at Boryspil, and Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty later managed to track down the real man associated with the account. He turned out to be Romanian, not Spanish, and he was not an air traffic controller.

Polygraph attempted to contact both “Ian56” and “Kat O'Hara” on Twitter for an interview. “Kat O’Hara” did not respond, but “Ian56” immediately added Polygraph’s Twitter account to several lists with titles such as “ISIS-terrorist-supporters,” “fascist-supporters,” and “american-traitors.” Polyraph.info asked “Ian56” to establish his identity or respond to an expert’s finding that he is a troll, a request the account’s operator ignored.

Cold War historians have extensively documented how the Soviet Union (as well as the U.S. and its Western allies) spread disinformation through covert channels. Oftentimes, this meant pushing a narrative through a foreign source not connected with the country of origin. One of the most famous cases was Operation: Infektion, a KGB disinformation campaign in the 1980’s aimed at spreading the idea that the HIV virus was engineered as a biological weapon by U.S. military scientists working at Ft. Detrick, Maryland.

That disinformation campaign, detailed in the CIA journal, Studies in Intelligence, began by planting an article in an obscure Indian newspaper. Experts in disinformation point to the internet and social media as the vehicles that make it easier now to plant, spread, and amplify disinformation.

Accounts like “Ian56” can pose as concerned citizens or independent journalists who post pro-Kremlin narratives, and then be cited by Russian state-funded news outlets such as Sputnik, in order to create the impression that the story originated somewhere else, or that a lot of people worldwide are discussing this narrative, thus lending it more credibility.