Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov made the comments on February 28 at the U.N. Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. The conference serves as an international venue to discuss issues and policies in the field of arms control, disarmament, and nonproliferation.

Branding the presence of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) in Europe and NATO training in the use of the weapons against Russia as “an aggressive stance,” Lavrov said Russia has not deployed such weapons or conducted the relevant training.

He also talked up Russia’s contribution to disarmament compared to that of the U.S., saying it has reduced its nuclear arsenal by more than 85% since the Cold War and is concerned about the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review outlining the U.S. nuclear doctrine.

“We are also concerned by a considerable shift in the US approaches in the context of the updated Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) which provides for a greater role of nuclear weapons,” he said, adding that U.S. plans for low-yield warheads would increase the risk of nuclear weapons use.

The NPR, which the U.S. adopted in February, calls for modernization of the aging U.S. nuclear arsenal and developing low-yield TNWs to provide for more flexible nuclear deterrence.

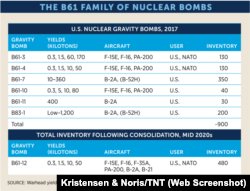

As part of the modernization, the U.S. will modify the 150-200 TNWs it deploys in Europe to reduce their yield and increase their precision, allowing for their battlefield use. The plan is to consolidate all the B61 variants versions into the new B61-12 nuclear gravity bomb, to be deliverable by both tactical and nuclear aircraft. The weapons could be deployed as early as 2020. Overall, the total inventory of nuclear gravity bombs will be reduced by nearly 50 percent by the mid-2020s.

The U.S. views it as critical to enhance both its conventional and nuclear capabilities in Europe given Russia’s overwhelming advantage in conventional forces and Russia’s outsized arsenal of almost 2,000 TNWs, which experts say also provides it with qualitative advantages.

Russia, in turn, views its arsenal of TNWs as necessary to counter NATO’s alleged superiority in conventional forces, despite reports indicating that the arrangement of forces favors Russia. And while Russia has arguably reduced its reliance on nuclear weapons given the modernization of its conventional forces, it continues to rely on TNWs for deterrence.

According to Michaela Dodge, a defense expert at the Heritage Foundation, the U.S. deployed its TNWs in Europe in 1953 “to counterbalance a massive Soviet conventional superiority” but withdrew 90% (some estimates say 97%) of its nuclear weapons after the end of the Cold War.

“Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. and NATO further decreased the importance of TNWs in their strategic doctrines and failed to modernize their TNWs. Russia, on the other hand, has modernized its TNWs,” she said. She writes that the failure of Russia and the U.S. to abide by their political commitments has “left the U.S. with as much as a 10-to-1 disadvantage in TNWs.”

The idea behind the NPR’s focus on the TNWs is to deny Russia the perception that its use of TNWs would provide it with a quick victory without triggering a nuclear response.

“Russia must instead understand that nuclear first-use, however limited, will fail to achieve its objectives … and trigger incalculable and intolerable costs for Moscow,” the review noted.

“This strategy will ensure Russia understands it has no advantages in will, non-nuclear capabilities, or nuclear escalation options. Correcting any Russian misperceptions along these lines is important to maintaining deterrence in Europe and strategic stability,” it added.

Some experts say the modified TNWs would provide the U.S. with more options to counter Russia’s capabilities given Russia’s nuclear modernization, which started earlier, and its military campaigns in Georgia and Ukraine, which threatened European NATO allies.

Others note the U.S. strategic nuclear capabilities provide a sufficient deterrent, arguing that enhanced reliance on TNWs lowers the threshold of their use and risks an all-out nuclear war, as Russia’s doctrine allows for a nuclear response regardless of the type of the nuclear attack.

“Any use of nuclear weapons against Russia or its allies, weapons of short, medium or any range at all, will be considered as a nuclear attack on this country. Retaliation will be immediate, with all the attendant consequences,” President Vladimir Putin told Russia’s parliament on March 1, boasting of five nuclear weapons systems Russia has developed or is developing.

The mismatch in perceptions and capabilities given the absence of arms control agreements specifically covering the TWNs, as well as arms developments and alleged violations of arms control treaties by both Russia and the U.S., have undermined disarmament efforts.

Both Russia and the U.S. have acknowledged the issues, but the efforts toward any accord are stalling.

Evan Montgomery, a senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, told Polygraph.info that Moscow has been reluctant to incorporate TNWs into an arms control regime. He also pointed to Russia’s violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), saying it suggests Russia is not genuinely interested in disarmament.

Russia, in turn, has accused the U.S. of violating the INF Treaty and the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which prohibits transferring nuclear weapons, or control over them, to other recipients. The Russians point to the U.S. deployment of TNWs in Europe as well as “joint nuclear missions” involving training with non-nuclear armed NATO allies as evidence. However, Montgomery told Polygraph.info that these arrangements “pre-date” the treaty.

Moreover, the U.S. TNWs remain in the custody of the U.S. military, and their use in a conflict would involve an agreement between the U.S. and the host countries, which include Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and Turkey. Just like Russia, the U.S. and host countries are involved in exercises and contingency planning likely involving the use of nuclear weapons.

NATO allies have reportedly participated in the “preparation and execution of the nuclear mission.” And while related training decreased in frequency with the end of the Cold War, the latest geopolitical and military developments could make them a higher priority for NATO.

“Although it remains the policy of NATO not to target its nuclear forces at any specific country, the policy does not preclude the possibility (or even likelihood) that contingency plans exist,” wrote Simon Lunn, who served as head of plans and policy on NATO’s International Staff.

The Pentagon declined to comment on Lavrov’s allegations.