Southern California’s two great cities, Los Angeles and San Diego, are pursuing different but equally cutting-edge solutions to the state’s epic, four-year drought.

The extreme dry spell, called a 500-year event, follows previous droughts in the early 1990s that galvanized local officials to invest in pioneering water delivery and storage systems on an unprecedented scale.

Their efforts are thrusting the two municipalities to the forefront of a growing number of cities reshaping urban water supply systems in drought-prone areas from Australia to the Middle East to the American West.

“The big story in Southern California is the move away from imported water to a more diversified supply,” said Stanford University’s Richard Luthy.

Los Angeles and San Diego were built with massive water infrastructure investments — reservoirs, dams and aqueducts — that continue to bring water from Northern California, the eastern Sierra and the Colorado River, sources more than 300 kilometers away.

But that’s changing, as supplies dwindle and prices rise.

“By 2025, we plan to reduce our purchases of imported water by half,” said Marty Adams, director of water operations for the influential Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), the largest municipal water agency in the United States.

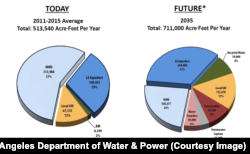

Now, 58 percent of L.A. County’s water is imported, with 38 percent coming from local groundwater sources, and only 4 percent from recycling, according to a University of California-Los Angeles study.

The numbers for the city of Los Angeles are even starker — about 86 percent of its water is imported.

Determined to change that equation, L.A. has embarked on huge wastewater recycling, stormwater capture and conservation projects.

One of those, an advanced water purification facility scheduled for completion in 2022 at the Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant, would add 30,000 acre-feet (37 billion liters) of recycled water to the city’s San Fernando Groundwater Basin.

The basin is located in the San Fernando Valley and supplies 80 percent of the city’s groundwater.

Los Angeles currently recycles about 8,000 acre-feet (10 billion liters) of water per year.

Most of it is used to irrigate golf courses, parks and cemeteries and meet industrial needs through so-called purple pipe systems that carry wastewater filtered for solids and cleaned of some impurities.

LADWP is also in the pre-design phase to build the world’s largest groundwater treatment center over a huge swath of contaminated aquifers, also in the San Fernando Valley.

The area is one of the Environmental Protection Agency’s largest Superfund pollution sites in the U.S. and contains scores of underground wells closed since the 1980s.

The Valley is about 200 meters higher than the coastal area where the city’s main sewage treatment facility, the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant, is located.

“If we did the same thing at Hyperion, getting the water back to the rest of L.A. would be incredibly expensive,” Adams said. “Our goal is to catch water as high up in the system as possible.”

That’s why the city purchased a 46-acre (19-hectare) former landfill in the Sun Valley area and plans to convert it into an engineered wetlands park that will collect stormwater and pump it into those same underground basins.

“The treatment center will recover the full use of groundwater aquifers lost to contamination and retain extra capacity to pump out the additional recycled water and stormwater we’re looking to capture,” Adams said.

Meanwhile, L.A.’s conservation efforts are also showing results, according to officials with the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County.

“We’ve seen our [sewage] flows drop 20 percent since 2005 together with steady population growth,” said Robert Ferrante, the Sanitation Districts’ assistant chief engineer.

But despite the success of L.A.’s award-winning sustainable water management programs, the region’s per capita water use is still twice as high as that of the average European city, the UCLA report says.

“L.A. has a long way to go to reach the efficiency levels of countries like Australia and Israel that have a similar climate and lifestyle but use a fraction of the water we do,” said Conner Everts, executive director of the Southern California Watershed Alliance, an environmental group.

San Diego bets on desalination

San Diego’s flagship effort, a controversial $1 billion seawater desalination plant in Carlsbad, is set to go online by the end of December and provide 7 to 10 percent of the county’s drinking water by 2020.

The ultra-modern, private facility — the largest in the Western Hemisphere — is seen by local officials and industry insiders as a counter to critics who say such projects are expensive, require huge amounts of energy and damage the environment.

“All the inexpensive water is gone, and the new supply — especially if drought-proof and locally controlled — costs more than conventional sources,” said Bob Yamada, water resources director at the San Diego County Water Authority.

“But Carlsbad’s cost increases are governed by contract, and we expect the price of treated imported water to equal or surpass that of desalinated water in the next 10 to 15 years,” he said.

Concerns raised by environmental groups about the impacts of seawater desalination — especially open-ocean intakes and concentrated brine discharge — helped push Los Angeles away from the technology, Luthy said.

Officials at Poseidon Water, the Boston-based company that built the Carlsbad plant, say their facility is state-of-the-art.

“It’s the most technologically advanced and environmentally sound desalination plant in the Americas and the latest one to come online worldwide,” said Jessica Jones, a Poseidon spokeswoman.

The San Diego authority is obligated to buy Carlsbad’s entire output of product water for 30 years through a purchase agreement with Poseidon.

For Everts, that’s just one of many red flags.

“Running a desalination plant is like buying an old Hummer [a large SUV] at peak gas prices, and being stuck with a 30-year lease [just makes it worse],” he said. “Beyond the environmental impacts, it’s just a bad idea.”

Australia invested more than $12 billion to build six desalination plants, four of which were shut down in 2012 when their Millennial Drought ended.

LA has groundwater, San Diego doesn’t

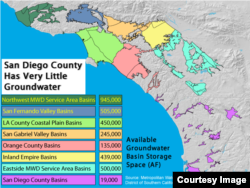

The most significant influence on the two cities’ choices is the fact that L.A. County’s extensive groundwater basins provide nearly 1.2 million acre-feet (1.5 trillion liters) of water storage versus just 19,000 acre-feet (23 billion liters) in San Diego.

“We looked at desalination, but given our geography and available resources, we have a lot more cost effective solutions available,” said Adams.

In San Diego, the Water Authority is running an aggressive strategy to diversify the region’s supply, including relining parts of the Coachella and All-American canals with water-saving concrete.

By 2035, local sources are projected to meet 40 percent of San Diego’s water demand, up from just 5 percent in 1991.

MWD’s giant recycling plans

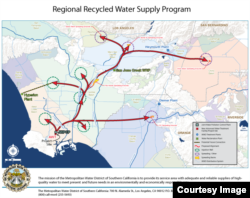

The region’s largest and most ambitious water reuse plan is moving into a pilot phase after preliminary approval last month by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the largest distributor of treated drinking water in the United States.

The massive importer, serving a six-county area and nearly 19 million people, partnered with the L.A. County Sanitation Districts to build what would be one of the world’s largest wastewater recycling systems.

By 2035, the project would purify up to 168,000 acre-feet (207 billion liters) of treated wastewater discharged each year into the Pacific Ocean and inject it into local groundwater basins before being pumped out and used as potable water.

For a look at why San Diego’s water authority is fighting Metropolitan’s innovative water reuse project, click here to see the first article in this two-part series.

LADWP, Metropolitan and the Sanitation Districts are currently discussing adding advanced treated water from Hyperion to the new system, pending its final approval.

"That’s a lot of water to push backwards into L.A.,” Adams said. “The best opportunity would be to add it to Met’s new pipelines.”

Orange County’s water and sanitation districts have run their own Groundwater Replenishment System — currently the world’s largest — since 2008.

Officials there hope a final expansion, planned for the next decade, would eventually treat and reuse all the Sanitation Districts’ effluent, about 49 billion gallons (180 billion liters) per year.

The MWD system would be technically similar — forcing wastewater through the same reverse osmosis membranes also used for desalination — but much larger in scale.

Both programs utilize so-called indirect potable reuse, where purified wastewater moves through a groundwater aquifer buffer before reaching those who drink it.

Direct potable reuse systems that put recycled water straight into a treatment plant’s supply have been approved for advanced treated wastewater in Texas.

“That’s a change, and it’s being studied in California,” said Luthy, who directs the National Science Foundation’s Engineering Research Center for reinventing the nation’s urban water infrastructure.

“Direct potable reuse has many advantages, including cost savings by circumventing injection into the ground or discharge to a reservoir,” he said. “In the coming years, we’ll likely see some version of that.”

This is the second article in a two-part series on how California is reshaping its urban water supply systems in the face of the state's epic drought. Click here for Part 1.