A violent mob assault on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad. The targeted killing of an Iranian general ordered by President Donald Trump. An accidental missile strike of a Ukrainian commercial airliner. A tightening of U.S. economic sanctions on Iran. The detention of the British ambassador in Tehran.

We are barely beyond the first week of a new year and a new decade, but already the alarming and chaotic news coming out of the Middle East makes it difficult not to feel a sense of foreboding for what's to come. Historical forces seem to be moving on paths impossible to identify precisely, but lead in the general direction of danger, political analysts and historians say.

And all this takes place at a time when the world already had plenty to worry about.

Trump has been impeached and awaits a trial seeking his removal from office that could begin in the Senate later this week. North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un continues to threaten the U.S. and has declared that he will no longer observe a ban on nuclear tests. Overseas, Australia is on fire. Britain is edging ever closer to Brexit.

A Middle East on the edge

With the crisis in the Middle East one miscalculation away from spiraling out of control, and a suite of other international fires to put out, many key posts in the Trump administration’s national security apparatus are filled by unconfirmed officials or sit empty altogether.

It’s little wonder that newspapers across the country are running stories on the rise in the number of people seeking mental health care for anxiety.

At times like these, a little historical perspective can be helpful.

Parallels to 1968

Robert Dallek, noted historian and author, points out that this is not the first time the United States has been beset by seemingly overwhelming problems.

"You know, we've been through many difficult moments," Dallek said in an interview with VOA. "Like 1968, when the country was locked into the war in Vietnam and you had inner-city riots, and [Lyndon] Johnson announced he wasn't going to run for president again."

At the time, a travel agency in France was pitching vacations in the United States with the tagline, "See America while it lasts," Dallek said.

"It was a time when people also thought that America was slowly coming to an end and might be heading into a new Civil War, and so there are echoes of that here," he said. However, he stressed that there are reasons to be hopeful. The United States did not descend into war, the war in Vietnam eventually came to an end, and civil unrest abated.

None of this, however, is to suggest that the real anxiety Americans feel is misplaced or imagined. Perhaps the most stressful issue facing Americans right now is the crisis unfolding in the Middle East.

Attack on US Embassy in Baghdad

On New Year's Eve, Americans woke up to the news that the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad’s Green Zone was under siege by a mob that had broken into a reception area and set part of the structure on fire. The protests followed a December 29 U.S strike against Iranian-backed Kataeb Hezbollah sites in Iraq and Syria in retaliation for the killing of a U.S. civilian contractor near the Iraqi city of Kirkuk two days earlier. The Pentagon announced that it was dispatching troops to the region, a number that quickly grew into the thousands.

Later on Twitter, Trump promised retribution if the attackers, reported to have connections to an Iran-backed militia group, harmed embassy personnel or damaged U.S. property. "This is not a Warning, it is a Threat. Happy New Year!" he wrote.

US drone strike on Soleimani

Two days later, shortly after landing at Baghdad International Airport, General Qassem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s notorious Quds Force, was killed in a drone strike that had been personally ordered by Trump.

Soleimani, who directed operations that have led to the killing of hundreds of American soldiers in Iraq and untold thousands of civilian deaths across the Middle East, was generally considered the second-most-powerful figure in the Iranian government.

Iran, promising revenge, observed three days of mourning for Soleimani before launching missiles at two installations in Iraq housing American military personnel. There was reason to believe that the missile strikes were more symbolic than dangerous.

But any hope that the limited Iranian response might reduce the tension in the region was dashed just hours later, when a Ukrainian jetliner with 176 travelers on board crashed outside Tehran. By the weekend, it had become clear that nervous Iranian air defense forces, on alert for U.S. retaliation after the strikes in Iraq, shot down the plane by accident, a fact that Iran eventually admitted.

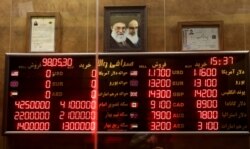

More sanctions for Iran

The United States announced Friday morning that it would impose new economic sanctions on Iran. These would come on top of existing penalties that Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has described as the most punishing the U.S. has ever levied on another country. Many Democratic lawmakers and some Republicans complained that Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other senior administration officials have misled Congress and the public in arguing that Suleimani had posed an “imminent” threat.

In Tehran on Saturday, the ambassador of Britain was arrested and held for several hours after attending a vigil for the 176 people killed in the attack on the Ukrainian airliner. The highly unusual step by Iran was accompanied by accusations that the diplomat incited street protests against the Iranian regime, a charge the British government hotly denied.

Within the U.S., the collective response to the unfolding crisis in the Middle East has been unease about where all this will end. Social media has been rife with references -- some joking, some not -- to an imminent World War III. But experts point out the likelihood of all-out war between the United States and Iran is low.

At the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank, professor of political science Michael Horowitz and senior fellow Elizabeth Saunders wrote Friday, “Blowback may be coming, and the U.S. strike against Soleimani may increase the risk of bad outcomes short of an all-out war. Those are reasons for concern. But it’s critical to distinguish such consequences from a general war.”

They added, "There will no doubt be consequences -- but general war remains unlikely."

A desire for 'normalcy'

Dallek, the presidential historian, said that in his view, the most likely outcome of a lengthy period of civic stress is an electorate primed for a return to perceived normalcy. This is something the Democrats are counting on as the 2020 presidential campaign heats up.

"I think the outcome of all this is going to be like in 1968, when the country wanted to get back to some kind of continuity," Dallek said.

It was that election in 1968, of course, that gave the United States the Nixon presidency.