On the 20th anniversary of NATO’s military intervention in Yugoslavia in March 1999, Russia’s Foreign Ministry issued a strongly worded statement denouncing it as an act of aggression against a sovereign European nation.

The Russian Foreign Ministry not only misrepresented the reason for NATO’s air campaign against Yugoslavia in 1999, but also substituted fact with fiction throughout the statement.

“The Autonomous Province of Kosovo was forcibly separated from the rest of the country under the propagandistic pretext of thwarting the allegedly unfolding ‘humanitarian disaster.’ In reality NATO became a trigger for a real human tragedy, a smokescreen hiding the anti-Serb ethnic cleansing that caused over 200,000 non-Albanians to leave their homes,” the statement read.

The Russian Foreign Ministry denied that NATO’s intervention came as a response to the unfolding ethnic cleansing of Kosovo’s Albanian population by the Serbian security services. We find this conclusion to be false, actually flipping the facts to claim that NATO provided a cover-up for the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo’s Serbs.

This part of Kosovo’s history, however, has been well documented. As international organizations and investigations of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia have found, the ethnic cleansing of the Kosovo Albanians started a year before NATO bombed targets in Serbia and Yugoslavia.

Apartheid-Style Rule

The Kosovo Albanians had “endured apartheid-style rule in virtual silence,” the International Crisis Group reported in March 1998.

Even when Serbia stripped Kosovo of its autonomy in 1989, Kosovo’s shadow president Ibrahim Rugova mounted a non-violent resistance to the state repression of the ethnic Albanians that demanded political rights and autonomy but not independence.

The Kosovo Albanians built a parallel society, with its own political structure, educational institutions, social aid networks, a shadow police force, and even a council for collecting taxes. This society existed completely outside the Serbian state, but its work was well documented. Albanian human rights organizations had collected thousands of pieces of documentary and photographic evidence of daily abuses by Serbian police in the province. Many of the archives were confiscated and destroyed by the Serbian authorities during raids and crackdowns on human rights defenders in Kosovo, but the documentation work continued. The founder of the Council for Defense of Human Rights and Freedoms in Kosovo, Adem Demaçi, showed this reporter the sizable archives of his organization in Pristina in June 1997.

One of Rugova’s main goals was that Kosovo’s autonomy, and the political rights of its Albanian population, be restored peacefully. He pleaded with the international community to negotiate with Belgrade on behalf of the Kosovo Albanians fearing that some of the restless and frustrated young Kosovars may resort to armed resistance (author’s interview with Ibrahim Rugova in June 1997). But when ten years of peaceful resistance did not gain sufficient international support to improve the situation of the Kosovo Albanians, the Kosovo Liberation Army was formed in 1996 and obtained arms from Albania, where scores of weapons had been looted during unrest in 1997.

The Bloody Crackdown

The plight of the Kosovo Albanians captured international attention on February 28, 1998 when Serbian paramilitary forces launched what the International Crisis Group called “a brutal offensive against alleged ethnic Albanian (Kosovar) separatists in Kosovo” in Drenica region that left 80 people dead, including children.

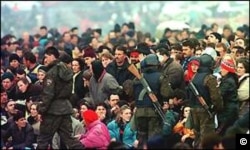

At that time, the Serb military police and the Yugoslav National Army started a campaign, with what a Brookings author described as “ham-fisted repression tactics” against civilians and the Kosovo Albanian armed insurgency. They killed innocent civilians and send a flood of refugees to neighboring countries -- 42,000 by June, 100,000 by August, and over 200,000 by October 1998.

Intensive international diplomacy and negotiations with Belgrade to prevent “another Bosnia” in the Balkans, including threats to bomb Yugoslavia, led to an agreement to allow a 2,000-strong Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe monitoring force in Kosovo to ensure Belgrade complied with UN demands.

Despite the presence of the OSCE Verification Mission and attempts by a U.S. congressional delegation to visit Kosovo (Belgrade blocked its entry), Serbian police atrocities against the ethnic Albanian population continued. In January 1999, the BBC publicized the gruesome pictures of what appeared to be a mass execution of 45 ethnic Albanians by Serbian policemen in the village of Račak, just 16 miles south of the capital, Pristina. BBC correspondents said that the victims, mostly men between the ages of 18 and 65, were not in uniform and most were too elderly to be Albanian fighters. A woman and child were reportedly among the victims.

This massacre sped up the international negotiations, but at the Rambouillet (February 6-23) and Paris (March 15-19) conferences, Serbia did not accept the Contact Group’s interim political settlement and NATO’s plan to enforce it with armed peacekeepers. The Contact Group was composed of the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and the U.S. NATO threats to start a military campaign against Slobodan Milosevic’s regime did not deter Serbia from launching “’Operation Horseshoe,’ a brutal offensive that displaced hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanians.”

Just two weeks before NATO’s military intervention, “Yugoslav forces poured into southwestern Kosovo,” reported the Baltimore Sun, “and shelled villages,” sending thousands of ethnic Albanians out of the area on tractor-pulled wagons. The situation with refugees at the border with Macedonia was already grim, said U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Sadako Ogata during a visit to Washington.

The NATO Intervention

Serbia’s failure to sign a peace plan for Kosovo and the acceleration of its military offense against the KLA and Kosovo Albanian civilians was the reason NATO launched air strikes against targets in Serbia and Yugoslavia. Its Operation Allied Force started on March 24, 1999. Human Rights Watch documented ethnic cleansing against the Kosovo Albanian population, that it assessed as planned by the Serbian authorities prior to NATO’s intervention. HRW reported that the abuses after March 20, 1999 were “a continuation and intensification of the attacks on civilians, displacement, and destruction of civilian property carried out by Serbian and Yugoslav security forces during 1998 and the first months of 1999.”

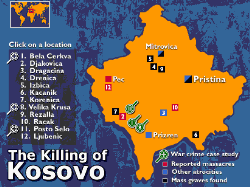

The humanitarian disaster unfolded when the OSCE withdrew its monitors four days before the bombing. Serbian police and military raided villages, rounding up ethnic Albanians and executing them en mass. The killings in the village of Bela Crkva, “planned well in advance, according to reporting at the time,” happened on March 24-25, as soon as NATO’s Operation Allied Forces began.

The list of Kosovo war victims, compiled by the Belgrade-based Humanitarian Law Centre and the Humanitarian Law Centre Kosovo, contains the names of 13,517 people who were killed or went missing between January 1998 and December 31, 2000, including civilians and members of the armed forces on both sides. The list includes 10,415 Albanians, 2,197 Serbs, 528 Roma, Bosniaks and other non-Albanians.

The majority of them were ethnic Albanian civilians, 8,661 people, who were targeted and killed by Serbian security forces before and during NATO’s intervention, which lasted 78 days. Most of the listed 1,797 civilian Serbs were killed or disappeared after the NATO operation when Serbian forces withdrew from Kosovo.

The unfolding ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, as the bombs were falling on Belgrade, Novi Sad and a number of military targets in Kosovo, was of such proportions that it turned between 1.2 and 1.45 million Kosovo Albanians into refugees in Macedonia, Albania and Montenegro or internally displaced persons.

Human Rights Watch wrote about the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo Albanians over the period of March – June 1999: “In the twelve weeks that followed, Serbian and Yugoslav military, police, and paramilitaries expelled more than 850,000 ethnic Albanians from Kosovo, internally displacing several hundred thousand more. Many were robbed and beaten as they were forced from their homes, which were frequently looted and burned. Scores of women were raped. Thousands of adult males were detained, and many of them were executed, in some cases together with women, children, and the elderly...In more than a dozen mass killing sites, government forces tried to hide the evidence by destroying or removing bodies. The brutal campaign against ethnic Albanian civilians came to a halt only after the withdrawal of Yugoslav soldiers and Serbian police and paramilitaries and the entry of NATO forces on June 12, 1999.”

Afterwards, around 150,000 Serbs and Roma left the province. Some of them were expelled by Albanians, while others, particularly local collaborators of the Serbian security forces, some of whom Roma, departed out of fear of revenge or fled from advancing NATO troops. According to the 1991 Yugoslavia census, there were 194,190 Serbs in Kosovo.

The European Center for Minority Issues estimated in 2013 that approximately 146,128 Serbs were residing in Kosovo. These statistics show that despite a sizeable exodus of members of the non-Albanian population after the conflict, the total number of Serbs living in Kosovo was reduced by about a quarter.

These events, as well as the previous developments related to the conflict in Kosovo, are described in great detail in Tim Judah’s book Kosovo: War and Revenge (Yale University Press, 2000).

Accounts by journalists, monitors and international organizations clearly show that the ethnic cleansing which took place before and during the Kosovo conflict was directed specifically at the ethnic Albanians, not at the ethnic Serb, though some KLA fighters were also implicated in war crimes. Crimes committed by Serbs against Kosovo Albanians were tried by the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague. In 2016, after the ICTY wrapped up its mission, a special tribunal was established in the International Criminal Court to investigate some members of the KLA for committing war crimes against ethnic minorities and political opponents.