Myanmar's military junta has blocked communication between detained pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her family and her lawyers, according to her younger son.

Suu Kyi's son Kim Aris told VOA via phone that the Myanmar junta has not allowed him to communicate with his mother "at all," despite concerns about her health.

Suu Kyi, 78, was arrested on February 1, 2021, after the military overturned the results of an election that her party had won. The coup was met with protests across the country and outrage around the globe. She received a 27-year sentence on what are widely seen as baseless corruption charges.

She was recently denied urgent medical attention for severe dental and gum problems that make it difficult for her to eat.

Aris said he sent her a letter and a care package about two months ago when he heard of her ill health.

"I have had no confirmation that she has received it," he said.

According to her son, Suu Kyi has not been allowed access to her legal counsel since at least January.

"She is not allowed to mingle with the other prisoners. She is essentially in solitary confinement," he said.

VOA has been trying to reach the junta's spokesperson since last Friday to follow up on Suu Kyi's case but has yet to receive a response.

At the end of October, junta spokesperson Major General Zaw Min Tun told VOA via phone that they would consider allowing Suu Kyi to see her family if they formally requested it.

Aris, however, said in the interview with VOA last Friday that the junta did not officially notify him through the relevant communication channels.

"The military issued some statement via the press that I could put in an official request," he said, "but they haven't actually approached me. … As far as I'm concerned, I don't trust what they're saying.

"They're not even allowing me to write to her. I don't see how I can put in a request to see her when that is the case," Aris added.

Communication blockade

Born and raised in the United Kingdom, Aris said he has used all official channels in his home country to try to reach his mother.

"I have been putting in requests via the British Foreign Office, the Burmese Embassy here and the International Red Cross for at least some communication with my mother since the beginning of the coup, and received absolutely no response," he told VOA.

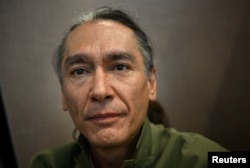

"According to the law [in Myanmar], there is a right [for prisoners] to have contact with family. Not allowing them to have contact with the outside world is a real violation of human rights," said Bo Kyi, a former political prisoner and co-founder of the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners, a Myanmar human rights monitoring group.

"The coup itself was a crime," Kyi told VOA, "therefore, the imprisonment of Aung San Suu Kyi was illegal."

He added that since the coup, "the military has been violating the constitution they themselves drafted. They are, in fact, committing treason."

The Myanmar Constitution, drafted in 2008 by a previous military junta, has come under fire from activists around the country, as well as the shadow National Unity Government (NUG).

The NUG has called for the "abolishment of the 2008 constitution," and a "national referendum to validate and enact the Federal Democracy Constitution developed by the Constitutional Convention," as outlined in their 2021 post-coup charter.