Growing up, Timothy “Twix” Ward, a member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe in Arizona, thought he was “normal.” But his family recognized there was something “special” about him.

“It wasn’t until I got older that I knew who I was, that I was different from everyone else,” he said. Ward identifies not as a man or a woman, but both — and neither: Twix Ward is a Two-Spirit.

The term was first devised in Winnipeg, Canada, during a 1990 inter-tribal conference of Native American/First Nations gays and lesbians. Derived from the Ojibwe language, the term was deliberately chosen to serve as a “pan-Indian” term encompassing indigenous people who don’t fit into any normative gender role.

“Two-spirited people are not LGBTQ [Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgendered or Gender Queer], although some two-spirited people are LGBTQ,” said Ward, narrowing the definition. “You’re not two-spirit unless you are familiar with your cultural identity and your traditions.”

Ward lives year-round in a traditional Apache house. He participates in traditional ceremonies. He is also a basket weaver and seamstress, specializing in basketry and making dresses for young Apache women’s coming-of-age ceremonies.

“I try to teach the girls what the dress is for, the meaning behind it in their ceremony,” Ward said.

But not everyone in the community accepts him, and he admits to loneliness.

“I still carry the traditional [two-spirit] face markings, the traditional attire,” he said. “Some people that claim to be traditional are upset with me because they think I’m acting like I know more than them.”

This year, the tribal council blocked him from using their facilities to hold a second annual “Miss Apache Diva” beauty contest.

Balancing the male and female

Thirteen hundred miles away in South Dakota, Kellie Bingen also identifies as a two-spirit bisexual. Born on the Lower Brule Reservation, she now lives in Sioux Falls, which makes her an “urban Indian," serving on the board of the Sioux Falls Two Spirit and Allies group.

“Two-spirits are people who can balance both their male and their female sides,” she said. “I’ve been a ‘tomboy’ my whole life. Dad taught us girls to do anything that a man can do, so we learned how to install sheetrock and to roof, and to fix our own cars.”

But she said she still has a “girlie” side. “I can wear heels and a dress, put makeup on, and go out and be pretty.”

Like Ward, Bingen believes only Natives who are in touch with their traditions can claim two-spirit identity — and the term should never be co-opted by non-Natives.

New York City musician and activist Tony Enos offers a slightly different interpretation.

“Two-spirit is a pan-Indian term for Native people who identify as gender queer, gender non-conforming, gender fluid,” he said.

Born to a biracial family and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he identifies as two-spirit based on paternal Cherokee ancestry.

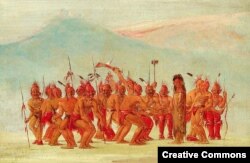

“Before colonization, we were balance-keepers. We were the only ones that could move between the men’s and women’s camps. There was a special role for these gender queer, gender fluid, gender non-conforming tribal individuals who had this special medicine, this blessing to be able to see life through male and female eyes.”

And that’s what the two-spirit movement is all about, he said — reclaiming the special role two-spirits held in pre-colonial tribal societies.

But is that even possible?

Decolonizing the ‘berdache’

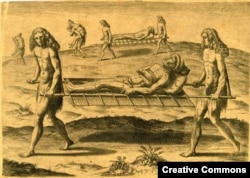

Much of what is known about historic two-spirits comes from accounts written by Western missionaries, adventurers and ethnographers, who referred to anyone who deviated gender norms by the derogatory term “berdache,” derived from the Arabic for slaves or kept boys.

Tribes had their own terms for third (if men) and forth (if women) genders -- “like a girl,” “manly-hearted woman,“ “both man and woman,” “fake,” “supernatural” or “instructed by the moon.”

In some tribes, two-spirits were considered sacred and were honored as healers, seers, name-givers, or in the case of the Yokuts and Mono of California, gravediggers, as they were believed to be guided by the dead.

“But not all tribes honored them,” said Wesley K. Thomas, a Navajo anthropologist, professor and graduate dean of the Navajo Technical University School of Graduate Studies and Research. He believes two-spirits tended to be honored only in matrilineal tribes like the Navajo, where descendancy is traced from the mother’s line.

In other tribes, they were merely tolerated.

“There were even some patrilineal tribal societies who committed infanticide of such children [early on] or later in life,” he said.

Whatever their status, the subjugation and Christianization of Indians by Europeans ensured that two-spirits were stamped out.

“As the country is gradually being filled with the Missions, these detestable people will be eradicated and that this most abominable of vices will be exterminated,” wrote Spanish missionary to California Francisco Palou in 1777.

By the mid-20th century, gay Native Americans, facing homophobia and ostracism within their own communities, began to flock to urban centers for safe haven.

“But there, they found themselves marginalized by non-Native LGBTQ communities,” said Thomas. Hence the need to name themselves.

Thomas isn’t critical of the two-spirit movement, which in his words “gives them a sense of belonging, of identity, self-affirmation.”

That said, Thomas doesn’t believe they will ever recover any honor given to them in the past.

“It’s not possible,” he said. “We have been distanced too much from our traditional ways and cultures.”