Nearly 50 years after his death, a Missouri journalist who covered the early years of the Chinese Communist Party is still lauded by Beijing as the ideal foreign correspondent.

Edgar Snow, who interviewed Chairman Mao Zedong multiple times, is presented by the Communist Party as a “friend of China,” appearing in romanticized films and cited by officials who want more “Snows of this new era among foreign #journalists.”

He even appears on government-run tours for foreign media.

“We were taken on a trip organized by the State Council to Yan’an, the revolutionary site, where [communist leaders] hid out in the caves for several years, and Edgar Snow was front and center,” one foreign journalist based in China told VOA.

“They kept harping on Edgar Snow, and they kept harping on that revolutionary history,” said the journalist, who asked for anonymity because of safety concerns.

During celebrations for the Communist Party centenary this summer, the state-run China Daily announced the launch of the Edgar Snow Newsroom of the New Era, to be staffed – it says – exclusively by foreigners.

The stated aim of this newsroom is “to present a true, multidimensional and panoramic view of China,” according to a June 20 article from the English-language China Daily.

VOA made several attempts to interview a representative of the China Daily, but emails and calls were not answered.

Media strategy

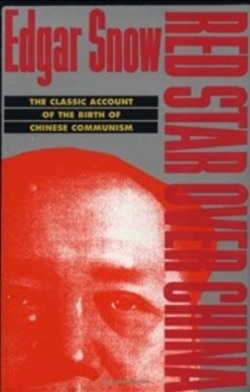

Beijing’s co-opting of the legacy of Snow, who is best known for his 1937 book Red Star Over China, comes as foreign correspondents are being expelled or limited in their reporting.

Political analysts and reporters who cover China see the Edgar Snow Newsroom as characteristic of Beijing’s broader efforts to influence foreign coverage and public opinion.

Julia Bergin, co-author of two reports on China’s global media influence for the International Federation of Journalists, believes the newsroom could be used to force foreign news media to increasingly depend on content from Chinese state-run outlets at a time when it is harder to secure a visa.

“If a major organization can't have a foreign correspondent based in China, and they can't be getting their own coverage of China, there is much more of a need, if they would like to cover China, to rely on that state content,” Bergin said.

China has developed content sharing agreements with dozens of international outlets as a way to export favorable coverage, IFJ research found. It has invested in equipment and studios for overseas newsrooms and runs exchange and training programs, often targeting journalists from countries that have weaker relations with the West.

Cédric Alviani, head of the East Asia bureau for media watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF), agrees that the newsroom “is totally consistent with China's global [media] strategy.”

“The Chinese regime has built such an impressive propaganda apparatus that it believes it doesn't need foreign correspondents anymore,” Alviani said. “So it just sees foreign correspondents as unwanted witnesses, and that’s the reason why it has started to get rid of them.”

Conditions for foreign media became tougher in 2020, as China and the U.S. engaged in a visa tit-for-tat following the Trump administration’s decision to curtail the number of Chinese staff at five state-controlled media organizations in the U.S.

At least a dozen journalists at U.S. outlets were expelled from China over the past 18 months.

A spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington told VOA via email that the country welcomes foreign media, ensures their "legitimate rights and interests," and that communication between reporters and authorities is "open and unfettered."

"As long as foreign journalists abide by the law and do reporting in compliance [with] the law and regulations, there is no need to worry. That said, we oppose any ideological bias against China, any attempt to fabricate fake news under the pretext of the so-called 'freedom of the press,' and any behavior that violates the professional ethics of journalism," spokesperson Liu Pengyu said.

The China Daily reported that the Snow newsroom will tell the “true” story of China. For Human Rights Watch researcher Yaqiu Wang, that’s code for disinformation.

“The Chinese government obviously doesn't want people to know the truth – the human rights violations committed in Xinjiang, in Hong Kong, in the mainland,” Wang told VOA. “They just want to create a story to cover up the truth that they know is true.”

Rebecca MacKinnon, CNN’s Beijing bureau chief from 1998 to 2001, believes an Edgar Snow Newsroom carries significant domestic propaganda value.

By attaching Snow’s name to the newsroom, the state is telling the Chinese population what the ideal foreign journalist looks like, perhaps to compel locals to speak only with foreign journalists who fit that manufactured mold, she said.

“Part of this may be further inoculating the Chinese public against journalists who are not like the cartoon version of Edgar Snow,” MacKinnon told VOA.

American abroad

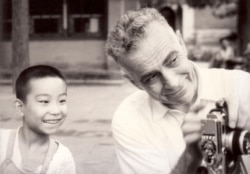

Snow covered China for the U.S. news magazine Saturday Evening Post at a time when few foreign journalists had access to the country and relations between the U.S. and China were essentially nonexistent.

As Bill Birtles, a China correspondent for the Australian Broadcasting Corp. who had to leave the country last year, put it, “Edgar Snow went off his own bat, traveled to China, and got an incredible scoop – the first inside account of the communist leadership.”

Back in the U.S., Snow’s close contact with the upper ranks of the party made him less welcome. He went into self-imposed exile in Switzerland because of McCarthyism – an aggressive U.S. campaign against communism in the 1950s – and died there in 1972.

Snow’s critics argue that the journalist wrote overly favorably about the Communist Party and sacrificed ethics for access.

One of the most common critiques, said John Maxwell Hamilton, journalist and author of Edgar Snow: A Biography, is that Snow failed to report on the Great Famine. But, Hamilton said, Snow’s notebooks demonstrated his efforts to investigate the impending disaster.

The famine of the late 1950s and early ’60s led to the deaths of tens of millions of people as a result of policies under Mao’s Great Leap Forward campaign.

The foreign correspondent who spoke with VOA on condition of anonymity said Snow missed other important events, like the purges and the mistreatment of women. But, the journalist said, that doesn’t detract from the respect Snow deserves for contributing greatly to the world’s understanding of the Communist Party.

Hamilton, a Louisiana State University professor who previously worked in the State Department, said that Beijing has “recast Edgar Snow into effectively a propagandist for them.”

“The Chinese Communists want to use him, because they want to pretend that Snow was a certain kind of journalist – which he wasn't – who would write favorably about the Chinese Communists,” Hamilton said. “They have appropriated aspects of what Snow did and made him into somebody that he wasn’t.”

He added it was unlikely that Beijing would let a journalist like Snow into the country today.

David Bandurski, director of the Hong Kong-based China Media Project, which studies trends in journalism in China, put it more succinctly.

“The creation of a newsroom around the idea of Snow is simply the nostalgic gift-wrapping of an external propaganda campaign,” he told VOA.

The tug of war over Snow’s legacy is not lost on the journalist’s daughter, Sian.

“Far from being cozy with any leader, my father was alternately considered persona non grata in China [for his alleged bourgeois ideas] and in his own country [for his alleged communist ideas] simply because he insisted on speaking the truth to both sides, often at his own expense, and strove to promote mutual understanding at a time of nuclear brinkmanship,” Sian Snow told VOA.

She added that her father was not a communist.

Reporting restrictions

Snow had access that foreign correspondents of today say is no longer possible. Even finding locals willing to be interviewed is tough.

“It used to be easy to call anyone, even on relatively sensitive topics,” the anonymous journalist said. “And there was a willingness to talk to foreign media, which has just gotten worse and worse, by the day.”

Often a source cancels, even if the article is about a harmless topic. Foreign reporters are also called into informal meetings with representatives from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who criticize their coverage.

For others, delays in visas, security risks or expulsion mean they have to report from the outside.

Birtles left China in August 2020 at the advice of the Australian Embassy after Chinese security officials questioned him and arbitrarily detained Cheng Lei, an Australian working for the China Global Television Network.

“In China, if you have fewer foreign journalists, then you're going to have more reporting from outside the country. And therefore, you're going to have more assumptions made in that reporting,” Birtles said. “The more time you spend out of the country, the more you lose touch with how quickly things change.”

Snow’s daughter said that limited space for journalists does not reflect her father or what he stood for.

“Unfortunately, the current Chinese government does not allow freedom of the press, even though that freedom, along with others, is enshrined in its constitution,” she told VOA. “In that sense, the newsroom does not represent who my father was.”