The Russian business daily Vzglyad claimed on August 20: “Sofia, under pressure from the United States, has twice put an end to Russian projects – the South Stream natural gas pipeline and the Belene nuclear power plant (Belene NPP).”

In August, Polygraph.info debunked the claim that Bulgaria quit the Belene NPP project in 2012 under pressure from the United States. The analysis showed that Sofia abandoned the construction of Belene NPP, which started in 1981, because of high costs, inability to attract a major Western investor and Russia's unwillingness to share the project’s financial risks, not because of U.S. pressure. Russia’s state-owned Atomstroyexport inflated its cost projections three-fold, which caused two critical Western investors to pull out. One of them, Germany’s RWE, was a strategic investor with a 49 percent share in the nuclear power plant.

Vzglyad also claimed that Sofia ended the South Stream natural gas pipeline project under U.S. pressure.

That claim is false.

Russian President Vladimir Putin put an end to the project after years of disregarding the European Union’s competition rules and energy regulations.

In blaming Bulgaria for the project’s cancellation, Vzglyad is merely repeating Putin’s words and thus serving as a tool for disseminating the Kremlin narrative about South Stream’s demise.

The Russian Mega Project

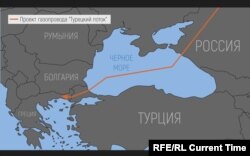

The Russian state-owned natural gas monopoly Gazprom announced in 2006 plans to builda pipeline under the Black Sea from Russia to Bulgaria, Serbia and Hungary, and eventually extend it to the Baumgarten Gus Hub in Austria. Moscow used the 2009 crisis involving gas supplies to Europe via Ukraine, when Gazprom stopped gas deliveries in the middle of a cold winter, to justify the project.

South Stream was designed to bypass Ukraine as a transit country for Russian gas, consolidate Russia’s grip on energy supplies to southeastern and Central Europe, undermine European anti-monopoly and energy legislation, divide the European Union by enticing some of its members with benefits from the pipeline, and compete with alternative gas supply projects like the Southern Gas Corridor from Azerbaijan.

But the project ran into two major problems with the European Union, which, since the first natural gas supply crisis in 2006 -- also caused by Gazprom-- had been working to improve its energy security by curbing energy supply monopolies and diversifying gas deliveries.

Moscow attempted to build the pipeline in violation of EU competition and anti-monopoly rules as well as in breach of the Third Energy Package adopted in 2009.

Evading EU Completion Rules

In its South Stream dealings with individual countries, Moscow attempted to avoid transparency and accountability to the European Commission. The South Stream project involved separate agreements with each participating transit state, which were not public. There was never a multilateral agreement or any attempt to reach an agreement with the European Union. Working on a bilateral basis with individual EU members was the Kremlin’s chosen way of doing business, and this was later replicated in the Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream natural gas pipeline projects. In 2013, the European Commission found these bilateral deals in breach of EU laws.

The South Stream pipeline was divided into separate sections for each country, which were managed by joint ventures between Gazprom and the national gas companies of those countries. While Gazprom and Bulgargas had equal shares in South Stream Bulgaria, in Serbia, Gazprom had 51 percent in the joint venture with Srbijagas. Each joint venture was established without a public procurement tender that would have opened it to other European companies. Nevertheless, the joint ventures were supposed to finance, build, and operate the South Stream pipeline section in each country.

The European Commission objected to this arrangement and called on South Stream participating states, all of which were either EU members or part of the European Energy Community (now the European Energy Union), to comply with EU rules.

But on May 27, 2014, South Stream Bulgaria, the Gazprom-Bulgargas joint venture, awarded a contract for the Bulgarian portion of the pipeline to the Russian company Stroytransgaz Holding. The major shareholder of Stroytransgaz Holding (63 percent) is the Volga Group, owned by Gennady Timchenko, who was placed on the U.S. sanctions list on March 20, 2014. Timchenko is a close friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin and was, at the time he was added to the U.S. sanctions list, ranked by Forbes Magazine as Russia’s sixth richest man. His Volga Group and another ten related entities, including Stroytransgaz Holding, were also sanctioned by the US Treasury Department on April 28, 2014.

Apparently the decision to award the construction contract for the Bulgarian portion of South Stream to Russia’s Stroytransgaz Holding was made an hour before European Commission President José Manuel Barroso met with Bulgarian Prime Minister Plamen Oresharski to warn him that the EU would impose penalties on Bulgaria if pipeline construction began in breach of EU laws.

Following those developments, the European Commission launched an infringement procedure against Bulgaria and suspended EU funds to the country. Faced with significant potential fines, Bulgaria suspended construction of the South Stream natural gas pipeline on June 8, 2014 to bring it into compliance with EU laws.

Instead of working with Sofia and Brussels to mitigate the problem, Putin canceled the project altogether five months later and announced the construction of a new pipeline to Turkey instead.

The Russian media proclaimed that the South Stream project was a victim of European politics.

South Stream and the Third Energy Package

The South Stream pipeline project embodied everything the EU was trying to prevent from happening in the European gas market by adopting the Third Energy Package.

That legislative package introduced a clear separation of natural gas production and supply activities from gas network operation, as well as a more effective regulatory oversight by independent national energy regulators and a reinforcement of consumer protection. LINK

The EU requires unbundling energy producers and suppliers from network operators. Gazprom wanted to be both the supplier of natural gas and the owner and operator of this major transportation infrastructure in Europe, thus creating a monopoly.

The EU requires allowing access and reserving capacity for third party suppliers to all pipelines on EU territory, including those coming from non-EU states. Gazprom wanted to retain its position as the sole gas supplier while remaining a pipeline owner and refusing to reserve capacity for any other gas supplier.

Gazprom also wanted to retain control over determining the gas transit fees paid to each country instead of allowing an independent national regulator to regulate those fees (which are supposed to only cover network maintenance and repair costs).

South Stream Suspension and Cancellation

The EU adamantly opposed the South Stream project on the grounds of the Third Energy Package. However, in the end, the European Commission’s infringement procedure against Bulgaria for establishing of a joint venture between Gazprom and Bulgargas in violation of EU competition rules proved to be decisive. Following Bulgaria’s suspension of the project in June 2014, President Putin canceled it in December of that year, blaming Sofia for its demise.

By that time, it had become clear that Gazprom would not be able to overcome the EU’s opposition to the pipeline and was unwilling to implement drastic changes to obey by EU laws. Moreover, an anti-monopoly probe the European Commission had started against Gazprom was threatening to result in serious fines.

But most importantly, by the end of 2014, the Western sanctions against Russia for annexing Crimea were hitting Moscow’s ability to access international financing, while oil prices were plummeting, shrinking Russia’s energy revenues. These two major developments were the deeper reasons for South Stream’s cancellation.

Polygraph.info finds Vzglyad’ s claim that Bulgaria put an end to the South Stream pipeline project to be false. The real reason the Russian president canceled the project was Moscow’s reluctance to conduct business in Europe by Europe’s rules and its inability to raise funds for the $40 billion project in the aftermath of the Western sanctions imposed on Russia for its March 2014 annexation of Crimea.