Death row inmates Patrick Murphy and Domineque Ray each turned to courts recently with a similar plea: Halt my execution if the state won’t let a spiritual adviser of my faith accompany me into the execution chamber.

Both cases wound up at the Supreme Court. And while the justices overrode a lower court and allowed Ray’s execution to go forward in Alabama in February, they gave Murphy, a Texas inmate, a temporary reprieve Thursday night.

What the justices wrote suggests the opposite results came down to one thing: timing. Ray, a Muslim, didn’t ask to be joined by his spiritual adviser soon enough, while Murphy, a Buddhist, did.

Issue raised too late

Spencer Hahn, one of Ray’s attorneys, said in a telephone interview Friday that he hoped his client had helped bring attention to the fact some inmates are treated differently when it comes to religious advisers in the execution chamber.

“I’d like to think Mr. Ray’s death was not in vain,” he said.

Hahn said the Supreme Court’s action in Murphy’s case sends a message to other corrections departments: “The Supreme Court doesn’t want to see people mistreated like this in their final moments.”

Ray, 42, was sentenced to death for the 1995 rape and murder of 15-year-old Tiffany Harville. His attorneys argued that Alabama’s execution procedure violated the Constitution by favoring Christian inmates over Muslims. A Christian chaplain employed by the prison is typically present in the execution chamber during a lethal injection, but the state would not let Ray’s imam in the chamber, arguing only prison employees are allowed for security reasons.

A federal appeals court halted Ray’s execution, but the Supreme Court reversed that decision and let it take place Feb. 7. The court’s five conservative justices said Ray waited until just 10 days before his execution to raise the issue. The court’s four liberal justices dissented. Justice Elena Kagan wrote that Ray’s request to have his imam by his side was denied Jan. 23 and he sued five days later. Ray’s imam watched the execution from an adjoining witness room.

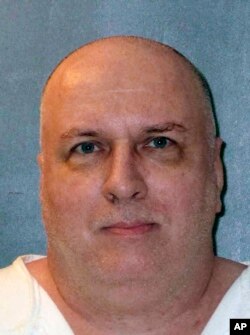

Murphy’s plea was similar. The 57-year-old, who was among a group of inmates who escaped from a Texas prison in 2000 and then committed numerous robberies, including one where a police officer was fatally shot, became a Buddhist while in prison. He asked that his spiritual adviser, a Buddhist priest, accompany him into the execution chamber. Texas officials said no.

They argued that only chaplains who had been extensively vetted by the prison system were allowed in the chamber. While Christian and Muslim chaplains were available, no Buddhist priest was.

Religious rights

Murphy’s lawyers argued that violated their client’s rights. Justice Clarence Thomas and Justice Neil Gorsuch would have allowed Murphy’s execution to proceed. But a majority of the Supreme Court said the state can’t carry out Murphy’s execution at this time unless it permits Murphy’s spiritual adviser or another Buddhist reverend the state chooses to accompany him in the execution chamber.

Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Jeremy Desel said Thursday that the state would review the ruling to determine how to respond.

Speaking just for himself, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote “that Murphy made his request to the State in a sufficiently timely manner, one month before the scheduled execution.” No other justice wrote separately.

Kavanaugh said the state has two options going forward: allow all inmates to have a religious adviser of their religion in the execution room, or allow religious advisers only in the viewing room, not the execution room.

Timing or something more

Robert Dunham, the head of the Death Penalty Information Center, said it’s possible something besides timing was considered by the justices.

“The more centrist conservatives on the court may have been stung by the overwhelming criticism they received from people across the political and religious and ideological spectrum” following Ray’s execution, he said.

It was not clear how many other inmates might find themselves in a similar situation. Only eight states, including Texas and Alabama, carried out executions last year.

But law professor James A. Sonne, whose Stanford clinic has studied the issue of chaplains’ presence at executions, said most of the 30 states with the death penalty allow a chaplain of the inmate’s choice to be present at the execution, though that doesn’t necessarily mean in the death chamber. He called Thursday’s ruling a “sea change.”