Inside the cool but smoky confines of Johannesburg’s Radium Beer Hall, about 50 people gather to listen to a young woman South African music critics are calling one of the country’s best-ever folk artists.

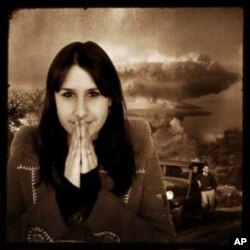

The raven-haired singer-songwriter, wearing knee-length boots and a stylish, sleeveless black patterned dress, sits cross-legged on a stool, guitar in hand. She smiles easily, jokes with her audience and exudes a gentle confidence.

The Radium’s one of South Africa’s oldest and most respected music venues, but Laurie Levine’s accustomed to even bigger things. Her fast-growing reputation has seen her perform at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. She’s played one of the most famous nightclubs in the world, New York’s legendary CBGB’s. She’s headlined The Forum in London. She’s opened for multiple Grammy-nominated English pop maestro Joe Jackson at Johannesburg’s Montecasino complex.

Yet Levine remains an entertainer of little pretence. During an interview following her gig at the Radium, a soft-spoken Levine stresses, “The music comes first, then the performer.”

‘Rebellion’ against past

Her new album is entitled Living Room. Levine explains, “It’s really a very intimate record. It’s a record that was produced with the intention of creating a very live feel, a very organic feel.”

In Levine’s quest to make “organic” music, she’s placed herself within an international musical movement that in recent years critics have labeled “Nu-Folk.” All over the world – but especially in the United States – there’s a sudden upsurge of quality folk, folk-rock, country-folk and Americana artists. These musicians are largely abandoning computerized effects and “plastic” over-production in their recordings, in favor of simple, “raw” sounding music using “real” instruments and thought-provoking lyrics.

Levine reflects, “I think it’s got to do with a rebellion against the past. In the past, we had this explosion of technology available to musicians and you could basically make any sounds you wanted just by pressing computer buttons. But I think a lot of modern musicians are realizing that this is an artificial way of making music. They now seem to desire a purity that perhaps wasn’t there before.”

On Living Room, Levine collaborated with highly acclaimed South African producer Dan Roberts.

“We really tried to capture the spirit of the songs using a huge variety of instruments, such as mandolin and banjo and accordion. So in that sense it’s a bit more experimental for me than my previous work and it’s a bit more rooted in folk and country,” she says.

Levine’s fresh approach, using her jazzy, soulful voice, has seen her latest album nominated for a South African Music Award, just as her first was.

No ‘fancy’ effects

“Dan Roberts works a lot with microphones close up to the instruments. He says he likes the instruments to ‘breathe,’” she says. “You can really hear the sound of the strings being played and pressed, and you can hear the breath when I’m singing.”

Both Levine and Roberts share a mission to capture the “natural” sounds of each instrument. “We also recorded the whole sound (of Living Room) live, so you get that sense of a couple of musicians in a room playing a song. Then we layered it with other sounds.”

But they stayed away from fancy effects, the singer emphasizes.

“We didn’t use a lot of compression; we didn’t use auto tuning. We kept the sound very natural…. In my record you can hear a bit of the garden sounds because I recorded in a home studio. On one track we even used natural sound from the seaside.”

Levine writes songs about “pretty intimate, personal experiences. Stuff that’s unspoken, that’s in the subtext of what happens every day but that we don’t really talk about. My songs give voice to that.”

In her latest work, though, she sometimes transcends the personal to tell the stories of women who exist on the “fringes of society.” In her song, “Nameless Face,” for example, she focuses on a sex worker, a homeless person and a cleaner.

From Steve Earle to Tinariwen

As much as the artist recognizes that she’s part of a new musical progression, she also acknowledges some of her influences are rooted “firmly” in the past.

“It’s really looking back to some of the songwriters who have inspired generations of singers – like Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen – and taking those influences and blending them with a contemporary sound,” Levine maintains, adding, “Someone who does that really beautifully is (American country-rocker) Steve Earle, because he’s really rooted in country. And yet on some of his albums he creates these beautiful loops which perhaps the Bob Dylan’s and the Joan Baez’s may not have used….”

Levine therefore describes “Nu-Folk” as “a blend of the old and the new and an experimentation of sorts.”

She also considers Tinariwen, the “rebel” Malian Taureg group, to be part of the current “organic” movement making “real” music, but with a “modern” feel.

Levine says, “That is quintessential African music but yet it’s so accessible to the rest of the world because it does have an almost electronic feel to it.”

African music

Although many of her influences are American, Levine maintains she’s “proudly” African.

“Africa represents so many different cultures; there are so many different influences (here) from all over the world – from blues to jazz to folk,” she says.

Levine adds that Africa’s “such an exciting place to be” because the continent’s musicians are willing to “amalgamate” so many different styles.

“Like Tinariwen, you’re blending your home influences with what you’re hearing from the rest of the world. You have a really beautiful blend of contemporary, western influences with deeply rooted traditional African influences. This makes it a very dynamic musical culture here in Africa.”

Levine comments that “no matter how big or small” she may become as an artist, she’ll always remain true to the “musical spirit” that’s alive inside her. “Sometimes, that’s the only thing that seems real to me,” she says…. And to the many thousands of people who’ve been moved by her extraordinary talent.