More than three weeks into the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, Washington's plans to help ensure the country does not descend into chaos remain murky despite a ramped-up effort to get Afghanistan's neighbors — Pakistan in particular — to do more.

The focus has been on rallying support, both for the ongoing diplomatic push to keep talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban on track, and for military cooperation should instability make new U.S. counterterrorism operations necessary.

But the U.S. efforts to solidify plans for what comes next appear to have taken on renewed urgency in recent days, leaning on outreach from the White House and the Pentagon to overcome a decade of strained ties and start to win over Pakistani officials.

Already, U.S. officials have voiced some optimism that an initial meeting between U.S. national security adviser Jake Sullivan and his Pakistani counterpart, Moeed Yusuf, on Sunday in Geneva, went well.

"Both sides discussed a range of bilateral, regional, and global issues of mutual interest," according to a statement issued by the White House on Monday, which made no reference to Afghanistan.

"Both sides agreed to continue the conversation," it said.

The Pentagon, likewise, expressed confidence following a call early Monday between U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Pakistan's Chief of Army Staff, General Qamar Javed Bajwa.

"The secretary's discussion this morning was very useful," Pentagon press secretary John Kirby told reporters. "The secretary reiterated his appreciation for Pakistan's support for the Afghanistan peace negotiations and expressed his desire to continue to build on the United States-Pakistan bilateral relationship."

History of mistrust

Yet beyond the initial discussions, progress on both the military and diplomatic fronts appears to be elusive, complicated by years of mistrust, some of it dating back to May 2011, when Washington did not alert Pakistan to the U.S. special operations forces raid in Abbottabad that killed al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden.

At the time, Islamabad warned the U.S. against any unilateral military action on Pakistani territory.

And Pakistan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs Monday rejected the idea of allowing the U.S. to use Pakistan as a base for troops or as a staging point for potential airstrikes, dismissing speculation about the possibility of such an arrangement as "baseless and irresponsible."

In an interview with VOA, Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi cast further doubt on how much help will be coming from Islamabad when it comes to ensuring Afghanistan is as stable as possible after U.S. and coalition troops leave.

"We have no business interfering in their internal matters, but we are there to help if they require our help, and we will try and be as positive as we can," Qureshi told VOA's Urdu service.

"Afghanistan is a sovereign country. It's an independent country," he said. "Whatever we can (do) we will, but they will have to ultimately shoulder the responsibility."

U.S. officials, though, continue to hope Pakistan will, in the end, be willing to do more, even if just out of self-interest.

"It has always been the case that Pakistan has much to gain from peace in Afghanistan," a State Department spokesperson told VOA on the condition of anonymity, given the sensitive nature of the ongoing discussions.

Other officials have expressed cautious optimism that self-interest, combined with encouragement, will sway officials in Islamabad to be more proactive.

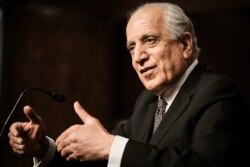

"I hope those with influence over the Taliban, such as Pakistan, do the right thing," Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. special representative for Afghanistan reconciliation, told U.S. lawmakers last week. "We are pressing them to do that."

Possible incentives

There are questions about how much leverage the U.S. can ultimately exert on Islamabad.

One option could be freeing up some $300 million in security aid to Pakistan that was frozen in 2018 under former U.S. President Donald Trump after his administration chastised Pakistan for a "dual policy of fighting some terrorists while supporting others" — a reference to Pakistan's ties to the Taliban and the Haqqani network.

U.S. officials will not say whether such a move is even under consideration.

"We do not comment or speculate on policies that may or may not be under deliberation," a State Department spokesperson told VOA — and even if it was, the money may not be enough to change Pakistan's thought process.

"It's complicated," a senior Pakistani official dealing with national security matters said to VOA about the aid. "We are not asking. If we get it, of course we won't say no."

In the meantime, U.S. options may be narrowing for its military posture once the withdrawal from Afghanistan is complete.

Russia's presidential envoy for Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, said Monday that Tajikistan and Uzbekistan will not allow the U.S. to establish military bases on their territories.

"They made it clear that this was impossible," he told the Russian news agency Sputnik, adding, "Our contacts with our Tajik and Uzbek partners indicate that there was no official request to them."

For their part, however, U.S. officials insist there is still time to work out agreements for the basing of troops and assets for when the pullout from Afghanistan is finally completed this coming September.

"These are obviously diplomatic discussions that are ongoing and are clearly not complete,' the Pentagon's Kirby told reporters. "We're exploring a range of options and opportunities to be able to provide a credible and viable over-the-horizon counterterrorism capability, and there's lots of ways you can do that. Overseas basing is just one of them."

Margaret Besheer at the United Nations, VOA Urdu Service contributed to this report.