SEOUL —

A scientific investigation has concluded one elephant has learned to speak at least six words of Korean.

He is Koshik, a 22-year-old resident of South Korea's largest theme park in Yongin, who can repeat with startling clarity - and matching both pitch and timbre patterns - what his trainer says, including "annhyeong," the Korean word for "hello" and "joah" - meaning "good."

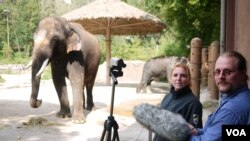

"We found that Koshik's imitations were very similar in the acoustic structure with the human vocalizations and very different from the ones that natural Asian elephants do produce," said cognitive biologist Angela Stoeger of the University of Vienna.

Stoeger is the lead author of a research article about Koshik appearing November 1 in Current Biology.

The researchers had native Korean speakers living in Germany, who were not aware of Koshik, listen to excerpts from 25 hours of audio tape of the elephant's voice recorded during October, 2010. The Korean speakers were able to write down precisely what Koshik was saying in their native language.

Stoeger said this is the first scientific evidence of vocal imitation for elephants and remarkable because his species usually does not make sounds at such relatively high frequencies.

"He's basically trying to match his vocalizations with his human trainers to be in social contact with them. It's a way of bonding with his people rather than using these vocalizations for their meaning," she explained.

In other words, Koshik likely does not actually mean what he utters.

Rather he is just imitating what he hears humans say.

Koshik's trainers first reported eight years ago that he was imitating speech.

There was anecdotal evidence of another, now deceased, male Asian elephant in a zoo in Kazakhstan who vocalized in Russian and Kazakh, but he was never scientifically investigated.

To create very accurate imitations of speech format frequencies, Koshik, according to the report in Current Biology “places his trunk inside his mouth, modulating the shape of the vocal tract during controlled phonation.”

The researchers assert this is a “wholly novel method of vocal production and formant control” never before seen in elephants or any other species.

Animal behaviorists said Koshik might have adopted his unusual vocal behavior because his only social contact for five years as a juvenile was with people.

Elephants in the wild are highly social. And, they do make sounds, including at very low frequencies which humans cannot hear, to communicate over distances.

Some researchers believe elephants may have distinct voices their kin can recognize.

"That's basically what I really now want to investigate," Stoeger said. "What we now saw, for example, in Koshik, how do they really use it for the natural communication system.”

Koshik is currently out of the public eye as his permanent home, 50 kilometers southeast of the South Korean capital, is closed to the public while it undergoes a renovation through next April.

He is Koshik, a 22-year-old resident of South Korea's largest theme park in Yongin, who can repeat with startling clarity - and matching both pitch and timbre patterns - what his trainer says, including "annhyeong," the Korean word for "hello" and "joah" - meaning "good."

"We found that Koshik's imitations were very similar in the acoustic structure with the human vocalizations and very different from the ones that natural Asian elephants do produce," said cognitive biologist Angela Stoeger of the University of Vienna.

Stoeger is the lead author of a research article about Koshik appearing November 1 in Current Biology.

The researchers had native Korean speakers living in Germany, who were not aware of Koshik, listen to excerpts from 25 hours of audio tape of the elephant's voice recorded during October, 2010. The Korean speakers were able to write down precisely what Koshik was saying in their native language.

Stoeger said this is the first scientific evidence of vocal imitation for elephants and remarkable because his species usually does not make sounds at such relatively high frequencies.

"He's basically trying to match his vocalizations with his human trainers to be in social contact with them. It's a way of bonding with his people rather than using these vocalizations for their meaning," she explained.

In other words, Koshik likely does not actually mean what he utters.

Rather he is just imitating what he hears humans say.

Koshik's trainers first reported eight years ago that he was imitating speech.

There was anecdotal evidence of another, now deceased, male Asian elephant in a zoo in Kazakhstan who vocalized in Russian and Kazakh, but he was never scientifically investigated.

To create very accurate imitations of speech format frequencies, Koshik, according to the report in Current Biology “places his trunk inside his mouth, modulating the shape of the vocal tract during controlled phonation.”

The researchers assert this is a “wholly novel method of vocal production and formant control” never before seen in elephants or any other species.

Animal behaviorists said Koshik might have adopted his unusual vocal behavior because his only social contact for five years as a juvenile was with people.

Elephants in the wild are highly social. And, they do make sounds, including at very low frequencies which humans cannot hear, to communicate over distances.

Some researchers believe elephants may have distinct voices their kin can recognize.

"That's basically what I really now want to investigate," Stoeger said. "What we now saw, for example, in Koshik, how do they really use it for the natural communication system.”

Koshik is currently out of the public eye as his permanent home, 50 kilometers southeast of the South Korean capital, is closed to the public while it undergoes a renovation through next April.