Tension in East Africa is rising after Ethiopia’s prime minister this weekend rejected Egypt’s suggestion the World Bank arbitrate ongoing disagreements over the construction of a dam on the Nile River.

The stakes are high for both countries. Ethiopia says the $5 billion hydroelectric dam will provide power to millions in desperate need of electric power. Egypt says it will disrupt the flow of water from the Nile, jeopardizing agriculture in the country.

Ethiopia anticipated the dam, now in its seventh year of construction, would be completed last year, but the project is only about 60 percent complete, according to the Associated Press.

The nixed arbitration is the latest setback in a months-long dispute between the regional powers. It’s also one of many regional conflicts heightened by a growing power struggle among Gulf states that continues to spill into East Africa.

If diplomatic tensions go unresolved, they could morph into military confrontations and proxy wars, say experts who closely watch the region.

Gulf crisis

East Africa has long faced a volatile mix of internal and external pressures, but Middle East states that see potential alliances in East Africa have complicated diplomacy in the region, according to Rashid Abdi, Horn of Africa project director at the International Crisis Group.

A major competition has emerged between several Arab parties, with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates on one side and Qatar and Turkey on the other.

“The Gulf crisis has simply, I think, brought out the long-simmering tensions between these regional powers. It is not the primary cause, but it is actually a potent catalyst of many of those fault lines, especially over the Nile waters,” Abdi said.

Turkey’s expanding role has had an especially destabilizing effect, he added. Turkey plans to build a naval dock in the Sudanese port city of Suakin, Sudan’s foreign minister said in December.

Last year Turkey built a military base in Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, to help train Somali soldiers in their fight against militant group al-Shabab.

Emerging powers

While Egypt and Ethiopia command most of the diplomatic clout in the region, other players see opportunities to assert themselves amid fresh tensions and a growing Arab presence.

Ethiopia and Sudan have developed a strategic alliance in the past year. Egypt and Eritrea have also grown close, with unconfirmed reports in recent weeks of Egyptian soldiers at the Sawa military base in Eritrea. Those reports might have been part of a “diversionary crisis” manufactured by Sudan, Abdi said.

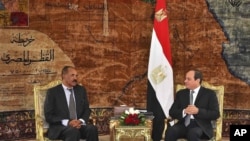

Earlier this month, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki met with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi in Cairo to discuss mutual interests.

For Sudan and Eritrea, the tension between Egypt and Ethiopia represents a chance to gain new footing and forge beneficial partnerships. Sudan faces a difficult road toward rebuilding its economy in the wake of lifted U.S. sanctions. Eritrea, still under sanctions, sees an opportunity to emerge from isolation and cope with its own vulnerabilities and migration issues, according to Abdi.

Hope for solutions

It’s unlikely Egypt and Ethiopia will go to war, Abdi said, as long as the countries use diplomatic channels and stay at the bargaining table.

“The destabilizing potential of the Gulf crisis can be discussed, but I think the more these discussions are in the open, [the more] that can probably modify behavior,” Abdi said.

But the possibility of military conflict persists.

“Unless, I think, there is an urgent understanding of the risks and also attempts to diffuse these tensions, I think there’s a likelihood we may see conflict, not immediately, but at some point,” Abdi said. “And I’m not necessarily talking about an open conflict between states but largely an escalation of proxy conflicts.”