In an interview published in the newspaper Moskovskiy Komsomolets on April 3, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov made it clear he considers the accession of Montenegro and North Macedonia to NATO to be a threat to Russia’s national security.

Lavrov expressed his country’s desire to be surrounded by a “belt of good-neighborliness” that does not contain the infrastructure of any military blocs. He claimed that NATO sees containing Russia as its raison d'être, as allegedly demonstrated by the expansion of the Western military alliance.

“When Montenegro and Macedonia were out of the blue dragged into NATO, the situation with Macedonia’s name was used in a brazen manner. They held a referendum organized in gross violation of the constitution, which in Macedonia requires a referendum to put forward only one question, but they put forward three: do you want to be a member of the European Union, a member of NATO, and are you ready to change the name of the country for that. In general, a fraudulent question, of course.”

We found this statement to be false, as were several other claims regarding NATO’s expansion that Lavrov made in the same interview.

One reason for our conclusion is NATO’s well-established policy and practice of only admitting new members that have passed a rigorous qualification process based on merit, commitment and readiness.

Furthermore, Russia has employed a strategy to prevent many countries in the former Eastern bloc from joining the Western military alliance or the European Union, while putting pressure on them to remain in Moscow’s orbit.

The strategy includes campaigns employing disinformation, social media manipulation, and bribes; inciting protests in North Macedonia and Greece in 2018; and even staging an assassination and coup d’état attempt in Montenegro in October 2017.

The NATO Admission Process

Prospective NATO members must apply to join the alliance, not the other way around. NATO only invites aspiring members after they have 1) demonstrated ability to contribute to the alliance’s collective security; 2) built a democratic system of governance and a market economy; 3) established civilian control over their military forces; 4) reformed their armies to be compatible with NATO forces; and 5) resolved any territorial disputes with their neighbors.

These initial minimal conditions were drawn up in the 1990s when, after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, countries from the former Warsaw Pact expressed interest in joining NATO. Subsequently, these conditions were expanded into Membership Action Plans (MAP) for each candidate state. These each involved five chapters: political and economic, defense and military, resources, security, and legal.

Developed together with the candidate country, the MAPs outlined specific steps in building a stable democracy, reforming the national armed forces, increasing defense spending, contributing to collective defense, as well as protecting sensitive information and bringing national legislation into line with that of the alliance.

Both North Macedonia and Montenegro had met their MAP requirements well in advance to receiving a formal invitation from NATO—and this was done voluntarily, regardless of the efforts and resources the process demanded. In fact, North Macedonia had fulfilled its MAP by the Bucharest Summit in 2008, when it was expected to receive an invitation. The only unresolved matter was the name dispute with Greece, which took another ten years to settle.

Montenegro’s road to NATO was neither shorter nor easier. Euro-Atlantic integration was a major driving force behind the country’s drive for independence from the former Yugoslavia. Separating from Serbia and distancing itself from Belgrade’s unwillingness to come to terms with the consequences of former Yugoslavia President Slobodan Milosevic’s nationalistic politics was a critical factor for the Montenegrin government in joining European and Atlantic institutions. But it was a difficult process that was resented by Belgrade and the Serbian minority in Montenegro. Eventually, the country held a referendum on independence, which, by an agreement with the EU, had to produce a 55% support for the vote to be considered valid.

Moscow’s Efforts to Thwart NATO’s Expansion

Lavrov still does not refer to North Macedonia by its new constitutional name. The country changed its name after signing a landmark agreement with Greece on June 17, 2018. The deal involved changing Macedonia’s name to North Macedonia in exchange for Greece’s full support for its northern neighbor’s NATO and EU accession, as well as recognition of the existence of the Macedonian nation and the Macedonian language.

North Macedonia will be the 30th member of NATO once all 29 current members ratify its accession protocol of February 6, 2019. Russia staged a disinformation campaign aimed at North Macedonia’s NATO and EU integration and paid various actors in both Greece and North Macedonia to stage protests and boycott the name deal.

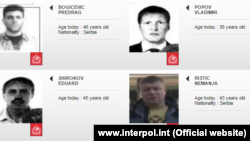

Moscow’s campaign to prevent Montenegro from joining NATO was even more disturbing. News reports and the government, itself, said two Russian military intelligence officers were involved in a conspiracy to assassinate Montenegro’s pro-Western President Milo Đukanović and fire at participants in a rally in the capital Podgorica in October 2017.

Montenegro’s ambassador to Washington, Nebojsa Kaludjerovic, told the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee on July 13, 2017 that the indictments issued in relation to the failed coup included two Russian nationals, members of the Russia’s military intelligence agency (GRU). Along with a few local politicians, they were indicted for conspiracy to form a criminal organization and stage a terrorist attack. Nine people agreed to a plea bargain admitting their guilt. “The witnesses identified one of the Russian nationals, former Deputy Military Attaché of [the] Russian Federation in Poland, who was declared persona non grata in that country for acts of espionage, as the organizer of the plot,” Kaludjerovic told the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee led by Senator John McCain at the time.

Russian Objection to NATO Presence in Eastern Europe

“As soon as a country is pulled into NATO, in the absence of any visible threats to its security, American military bases are immediately established on its territory,” Lavrov told Moskovskiy Komsomolets, adding that a third NATO-U.S. base is being built in Georgia. The Russian foreign minister omitted the fact that before NATO established any presence in Georgia, Russia invaded its province of South Ossetia and supported declarations of independence by South Ossetia and the Black Sea Georgian region of Abkhazia. His comments also exaggerated NATO’s presence in Georgia, as the alliance only has a liaison office in Tbilisi, not a military base.

Russia says its main concern is NATO’s military presence near its borders, because it wants a peaceful “belt of good-neighborliness” surrounding it. But Russia itself, has undermined the notion. It has supported secessionist movements and separatist wars in Moldova, Georgia, Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine. It became involved in direct military operations in Georgia and is staging a proxy war involving Russian soldiers in Ukraine.

While Lavrov says his country is only concerned about respecting the constitution of Macedonia and international norms, that does not square with Moscow’s demonstrated disregard for international law and the territorial integrity of Georgia and Ukraine, nor with the downing of the Malaysian airliner MH17 with 298 passengers on board by a Russian BUK missile in Donbas in 2014, and the thousands of people killed, injured and displaced by over five years of armed attacks in eastern Ukraine.

In the case of North Macedonia, Lavrov said that only President George Ivanov had the right to sign the agreement between Skopje and Athens. That is untrue: the Constitution of North Macedonia clearly states that the president represents the state and serves as commander-in-chief (Article 79), but executive power is vested with the government (Article 88), which is composed by prime minister and ministers (Article 89).

Among other duties, the government decides on the recognition of states and governments; establishes diplomatic and consular relations with other states; makes decisions on opening diplomatic and consular offices abroad. In addition, the government has the right, equal to the president, to propose associating in a union or community with other states or joining international organizations.

These are the principles of a parliamentary democracy, where the government makes the executive decisions and is accountable to the parliament, while the president has a mainly ceremonial role as the head of state in times of peace. This is markedly different from Russia’s “absolutist” presidential system or even the U.S. presidential system, under which a president is accountable to Congress.

Finally, Russia’s foreign minister is wrong in claiming that the question put forward in North Macedonia’s referendum was fraudulent. The constitution does not specify how many questions a referendum can put forward to the voters. Article 73 states: “The Assembly decides on issuing notice of a referendum concerning specific matters within its sphere of competence by a majority vote of the total number of Representatives.” The constitution does not mandate asking one or more than one question, or the combination of several questions. As long as the majority members of parliament approve a referendum “concerning specific matters within its sphere of competence,” the referendum is legal.