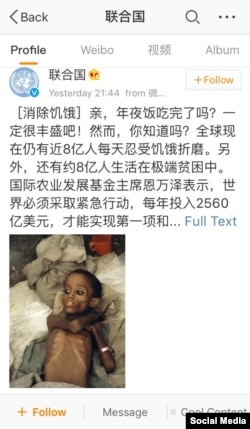

The United Nations has removed two Lunar New Year posts on refugees and poverty from its social media site on China's popular Weibo microblogging platform after the messages sparked strong backlash online.

Although the microblog messages were aimed at boosting awareness, many took the posts as a slight to China, arguing that the world's second largest economy has already done enough to contribute to the U.N. and was not a source of the problems - be it refugees or poverty.

Another world

In the first message that went up on the eve of the Lunar New Year, the U.N. post asked: “Dear, have you had your Lunar New Year’s dinner yet? It must have been some feast!” The post went on to talk about how some 800 million people in the world struggle with starvation every day and that the same number live in extreme poverty. The post also noted that $250 billion in funds is needed from around the world to achieve the U.N.’s sustainable development goal of eradicating poverty by 2030.

The second post, which came early on Lunar New Year Day, included a video that highlighted the sharp contrast between those living in conflict zones such as Syria and in refugee camps and those living elsewhere. The introduction read: “As the flowers of the Spring Festival blossom, let me take you to see another world…”

Before it was taken down, the video was viewed more than 10 million times and received more than 54,000 comments. Most were negative and many urged the United Nations to not send such messages to China, especially during the holiday season.

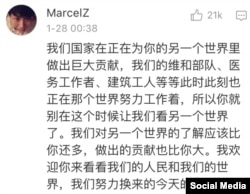

A post by MarcelZ that was liked by 21,000 argued that China was already doing plenty to help this ‘other world’ that the United Nations was sharing with the Chinese public.

“We know more about that other world than you and our contributions are even greater,” the post said, noting China’s participation in U.N. peacekeeping, medical and construction work. “At this time, we are already working for that world, so don’t come to us at this time and ask us to look at another world.”

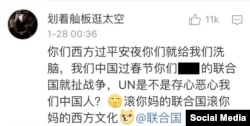

Another post, which had 11,000 likes, accused the U.N. of trying to brainwash the Chinese public with ‘western culture.’

“You (expletive) UN go and talk about war, while we enjoy our Spring Festival," the post said. “Does the U.N. harbor some ill will toward China?”

Unfairly targeted

Although neither of the posts suggested China was to blame, many Chinese saw them that way and argued that the United States and the west were the ones who should be receiving such messages on Facebook during their holidays.

“This is like sending pictures of a funeral during a wedding,” one noted.

The same post was not found on Christmas or New Year’s Day on the U.N.’s social media or Facebook sites. But on Twitter on Christmas Day, the United Nations did have two similar posts, one about Syria and another on poverty. Social media sites such as Facebook, Youtube and Twitter are blocked in China.

Of the two posts that went up in China on the U.N.’s Weibo account, one was a statement from a recent International Fund for Agricultural Development conference in Rome. The video was from the UNHCR, the U.N.’s refugee agency.

Unintended offense

In an emailed response about the online backlash, Peter Dawkins, the head of the United Nations web services, told VOA that while the messages reflected established U.N. positions, they were taken down after it quickly became clear that “the timing” of the release of the posts and “associated choice of imagery may have caused unintentional offense to some Chinese readers.”

“We have always appreciated our Chinese audience’s support for the work of the United Nations and will continue to try our best to live up to that trust,” Dawkins said.

In addition to the postings about refugees and poverty, the U.N. also posted several messages to mark the Lunar New Year, including a video from Secretary General Antonio Guterres in which he highlighted what he said was the vital role that China plays.

“I’ve called for 2017 to be a year for peace. We must work together to overcome conflict, human rights abuses, poverty and other crises,” Guterres said. “And above all we must work together to prevent these problems in the first place.”

Most of the comments in response to the video, however, continued to vent anger and frustration with the posts that had been removed.

“Just take care of America, that would be your greatest achievement,” one post read. Another said, “Thank you Secretary General, but we do not take refugees. Anything else though, can be discussed.”

One post did seem to respond to Gutteres’ challenge, urging the Secretary General to investigate what it called the “Communist Party’s bad behavior, including its encroachment on the human rights of its own citizens, and the Han people’s (China’s main ethnic group) racial prejudice.”

Bigger role

The online commotion comes at a time when U.S. President Donald Trump is facing mounting criticism at home over recently enacted immigration policies, and as China looks to play a bigger role on the global stage.

Reports have suggested that the Trump administration could make major cutbacks at the United Nations and Chinese officials are already beginning to hint Beijing is ready to fill the power vacuum that would leave in its place.

But so far, when it comes to money and playing a bigger role, the Chinese public seems hesitant and divided.

When Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered his first address to the United Nations in 2015 and pledged $2 billion for debt relief and assistance to poor countries, critics at home argued he had gone too far, noting that China still has millions of its own at home who live below the poverty line.

Over the past six decades, China has said it has contributed nearly $60 billion in aid to 166 countries and organizations around the world. But that’s less than what the European Union and its members give each year.

And when it comes to refugees, China has largely viewed the crisis as a problem created by Western nations. In 1982, China ratified the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. However, it was not until 2013 that a law went into practice that allowed public security officials to issue identification cards to refugees and asylum seekers.