Among the political and legal fights over U.S. elections, some of the most contentious ones center on voter identification requirements and on the way political districts are drawn.

Historically, both sometimes have been misused to suppress minority voting, which the Voting Rights Act of 1965 aimed to correct.

Voter ID

As of this spring, 32 states had voter identification laws in place; North Carolina will join them in 2016, the National Conference of State Legislatures reports. Most of the new measures have been introduced and implemented by Republican-led legislatures. While some states permit the use of bank statements, student IDs or other evidence of state residence, stricter ones require approved photo IDs, such as government-issued driver's licenses and passports.

Supporters say voter ID requirements battle fraud and build confidence in election fairness. Critics say that voter impersonation is rare and that the laws disproportionately discourage the poor, minorities, senior citizens and students from voting.

Someone born in the 1920s or '30s in a rural part of the country might not have a formal birth certificate, said Andra Gillespie, an associate professor of political science at Emory University in Georgia. "If your birth certificate is the family Bible, then that might not count as the official documentation you need" for voter registration.

Melvin Robertson understands that predicament. A resident of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he has voted for most of his 86 years.

"Got to vote – that counts!" Robertson said, suggesting that’s a true measure of citizenship.

But he may not be able to cast a ballot in the next election.

Strict rule in Wisconsin

Wisconsin has just enacted a controversial voter ID law. It was passed in 2011, pushed through the GOP-led legislature and signed by Republican Governor Scott Walker. It was halted by a series of legal challenges and even frozen by the U.S. Supreme Court last fall. But when the high court declined to hear the case, the law took effect after a statewide election in April.

Now, Robertson and an estimated 340,000 other state residents lack the proper documentation to vote. Robertson has a Social Security card and a city-issued ID. But when he tried to get a copy of his birth certificate at the Milwaukee County courthouse, there was no such record on file.

When Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker signed the law, he cited concern for voter fraud and support for election integrity as the motivations. Through its passage, he said, lawmakers were "making it clear we are protecting each and every vote…."

Incidence of voter fraud

Opponents cried voter suppression, saying there is almost no evidence of voter fraud in the state.

"Illegal voting of all kinds is extremely rare in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Government Accountability Board spokesman Reid Magney confirmed in an email to VOA. He said most infractions involve people on parole or probation who "have not had their civil rights restored yet."

The 2012 presidential election brought two such convictions, Magney said, acknowledging "there may have been more charges and convictions that we’re not aware of. Voter photo ID would not prevent this kind of illegal voting."

A Loyola University Law School professor found only 31 verifiable cases of in-person voter fraud – the kind that would be deterred by photo IDs – among roughly 1 billion votes cast nationwide from 2000 to 2014.

Walker, now a Republican candidate for the 2016 presidential election, has vowed Wisconsin will make every effort to ensure that legitimate voters have necessary identification, even if it means offering IDs at no cost to individuals.

"Everyone [who] is legitimate to vote will have easy access to do that," he said.

Anita Johnson is a Milwaukee community activist trying to help residents understand the recent changes in voting law.

"The reason why this law was changed, that we now have to show a photo ID, is to stop people from voting – plain and simple," said Johnson, an activist with Our Democracy 2020, a coalition of Wisconsin good government and pro-democracy groups. "It affects senior citizens, it affects students, it affects the low-income [people]. It affects people of color."

Question intent?

Republican Milwaukee County Election Commissioner Rick Baas takes issue with the idea that the law is unfair to minorities.

"Given that I am a part of that demographic, I find it offensive that somehow minorities are not bright enough to get an ID," he said. "… If you are American, I want you to vote.”

Gillespie, the Emory University professor, noted that her state of Georgia implemented a voter ID law in 2006, and “it has not had an adverse effect on African-American voter turnout so far.

"Once people get past the registration hurdle, voter ID laws are really not particularly consequential," she said. "It doesn’t mean that people can’t question the intent of the law."

But a U.S. congresswoman from the neighboring state of Alabama believes it's a deterrent.

Representative Terri Sewell said when Alabama implemented its voter ID law in 2014, she learned firsthand how challenging it could be. The Democratic legislator's father, normally confined to a wheelchair, had to be helped up the steps of the Dallas County courthouse – a historic building waived from federal access requirements – to obtain a photo ID. Sewell said the whole effort took several hours, "and he was motivated because his daughter was on the ballot."

Sewell, who worries such obstacles would discourage other voters, is sponsoring legislation to restore related Voting Rights Act provisions set aside by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013.

Watch related report by Chris Simkins:

Redistricting

Another hot-button issue involving voting rights is redistricting. The Constitution requires states to adjust voting districts and boundaries every 10 years, reflecting population shifts found in Census data. (An interactive game shows the challenges.)

In many states, district boundaries are drawn by lawmakers seeking a partisan advantage. The practice, known as "gerrymandering," takes its name from Eldridge Gerry. As Massachusetts’ governor in the early 1800s, he had the northeastern state’s district boundaries redrawn, and one resembled a salamander.

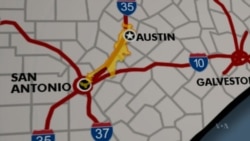

Some of the strangest-looking congressional districts are in Texas, where a legal fight continues over boundaries drawn by the Republican-controlled legislature in 2010. The courts are trying to determine if the redistricting maps violated provisions of the Voting Rights Act.

One-party rule

The state’s history of one-party rule has created bitter political fights over voter distribution, said Jim Henson, who directs the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin.

"For decades," he said, "the Democrats dominated that process and you had Republicans feeling prophetically bullied in the redistricting process."

Democrats are responsible for the upside-down elephant shape of the 35th District, which connects parts of Austin, the capital, with San Antonio some 129 kilometers or 80 miles to the south. In the early 1990s, they tried to corral as many liberal voters as possible into the district.

Larry Gonzales, a Republican in the Texas House of Representatives, represents a community where the redistricting plans that he helped design are being challenged. It includes Williamson County, which encompasses Austin’s northern suburbs. The county, still majority white, is 24 percent Hispanic and 7 percent black.

"When it came to drawing the lines for Williamson County, we understood that the population is diverse enough that we could draw the lines and still meet the requirements of the Voting Rights Act," he told VOA earlier this summer at the state Republican Party's headquarters.

Watch related report by Chris Simkins:

Political impact

In some cases, shifting political boundaries and practices have helped put minorities into public office.

In Austin, Sabino "Pio" Renteria is among three Latinos serving on the 11-member city council. The Democrat was elected in 2014 after the city did away with an at-large system and substituted one that fills council seats by geographic districts slicing around white and minority neighborhoods. He’d failed in a 1990 bid under the earlier system.

Constituents "worked the elections for single-member districts," Renteria said, noting he was "the first elected member from my district."

Renteria has a boyhood memory of the 1960 presidential election in Texas, where his father and other Latinos faced discriminatory voting practices.

"Back then, you had to pay poll taxes to vote. I remember going with my dad and [him] voting for John F. Kennedy and paying $2.50" – a hardship when he was earning $1 an hour and supporting a family of 10, Renteria recalled. "But he was determined to vote."

Five decades later, the political landscape has changed. But Renteria said he feared Republicans "are going to draw their lines so that they can stay in power for the next 20 to 30 years."

Instead, voters deserve to have political jurisdictions determined by nonpartisan citizen committees, Renteria said.

Independent commissions already are used by seven states: Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Jersey and Washington. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed their right to have them.

In the 5-4 vote, justices rebuked the challenge by Arizona’s Republican legislators.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, writing for the majority, said: “Arizona voters sought to restore the core principle that voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.”

Chris Simkins and Jeff Swicord reported from Georgia, Texas and Wisconsin. Carol Guensburg reported from Washington.