Americans mark this Independence Day during a time of turmoil in the United States.

While many debate whether to wear a mask in public, the COVID-19 pandemic is surging in most U.S. states. Outraged Black Lives Matter protesters have taken to the streets after the death of George Floyd while in police custody.

A staggering 42.6 million people have filed for unemployment benefits during the pandemic. The existing political divisiveness that was heightened by the 2016 election of President Donald Trump continues to rage into the last year of his 4-year term.

But the United States has faced great unrest, uncertainty and divisions before, and even in quiet times, discord is constantly rippling beneath the surface, according to sociologist Todd Gitlin of Columbia University.

Myth of unity

“America has always been divided. I think the myth of a unified country is a myth… American beliefs have been contested ground from the start,” Gitlin says. “I mean, pick a moment in history when we have always not been deeply divided.”

In her 244-year history, the U.S. has endured deep divisions between its political parties, and over industrialization, the Civil War, immigration in the late 1800s, women’s suffrage, whether to enter the first and second world wars, civil rights and anti-war protests in the 1960s, gay rights, abortion rights and numerous other battles.

“When have we not been deeply divided?” Gitlin asks.

One reason for that disunity could be found at the very foundation of America, a melting pot of people who do not share a common origin story.

“We're not just a normal nation founded on agreement on a national story or a national consensus, which are usually embedded in a story of national origins,” Gitlin says. “America is unified by an ideological doctrine. As a statement of belief, rather than a statement of identity.”

Common beliefs

America’s identity comes through the common beliefs laid out in the Declaration of Independence, which is celebrated on the Fourth of July. And using the holiday to air out one’s grievances is not uncommon.

“People in the country who have felt marginalized or oppressed or cut out of the American Dream have always used the Fourth of July as an occasion to claim their membership in the nation, to claim their freedom and liberty and their equality with others,” says Timothy Shannon, professor of history at Gettysburg College.

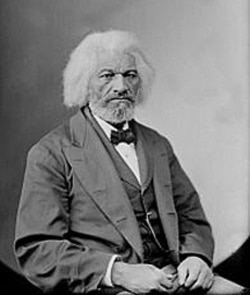

In July 1848, suffragettes launched the women’s rights movement with the drafting of a “Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances,” a treatise modeled on the Declaration of Independence. And, before there was a Labor Day holiday, the Fourth of July was central to the labor movement. On July 5, 1852, American abolitionist Frederick Douglass gave his now-famous speech that asked, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"

Founding fathers’ ideals

In praising the nation's founders’ ideals of freedom, the former slave-turned-prominent-activist pointed out the hypocrisy of their ideals due to the existence of slavery.

"Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” Douglass asked.

For some observers, today’s Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality and injustice recall the turbulent 1960s, when people marched for civil rights, women’s rights, and against the American war in Vietnam.

A history of protest

“In the 1960s, we saw protesters marching in the streets and people boycotting racist companies,” says Jamie Goodall, a staff historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington and a former assistant professor of history at Stevenson University in Baltimore, in an email sent to VOA.

“Today, we have protesters taking to the streets and individuals choosing to purchase from Black-owned companies, boycotting companies that contribute to racist and bigoted causes. We can look to these protesters as a sign of American resilience in the face of adversity. They’re carrying the torch of their predecessors, continuing the fight for freedom and equity,” Goodall added.

Gitlin believes America is in the middle of its latest existential crisis, which began in the early 1970s when the standard of living for most Americans stagnated or began to decline, while the wealth gap between the haves and have-nots widened.

Fight over facemasks

The fight over whether to wear a facemask to protect others against the spread of COVID-19 could come down to how Americans view themselves in a country that increasingly makes people feel like they have to choose a side.

“Are we freestanding, isolated individuals who are self-made and do not owe collective responsibility to those less lucky?” Gitlin says. “Or are we connected in ways that require some sort of coordinated response to avoidable individual suffering?”

Towards a more perfect union

In some ways, this Fourth of July — mired by a faltering economy, COVID-19, polarized politics, and protests against police brutality and for social justice — reminds America that although she hasn’t quite fulfilled her promise, the work towards achieving those ideals continues.

“It's kind of our annual reminder that the nation was founded on a pretty radical political principle: all men are created equal,” Shannon says. “That was not obviously the reality in 1776, in a country that had slavery, in a country where women were denied the right to vote… But, as a nation, we have been called to live up to that ideal, and to do our best each generation to promote and preserve that notion of equality.”