As Ethiopia prepares for parliamentary elections scheduled to take place in June, the contest to win the hearts and minds of voters is already under way on social media, which democracy activist Befeqadu Hailu is closely watching.

“Social media has offered us a means to organize, networking, and expressing ourselves safely, easily and cheaply,” he explained to VOA during a Skype interview from his office in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. “But on the other hand, the political organizations and political groups are using social media in an organized manner so they can disseminate any information in the interest of their political advantage, so that is manipulating their followers.”

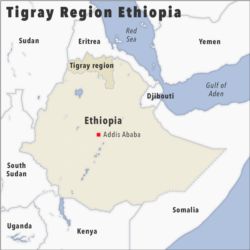

Ethiopian elections come as unrest flares in its northern Tigray region, where ethnic and political tensions are exploited online. Facebook is the dominant social media platform in the country, although less than 20% of the overall population has internet access.

“People disseminate whatever they hear on social media through mouth-to-mouth communication,” Hailu explained.

In October 2019, a disputed Facebook post by a well-known Ethiopian media figure went viral, prompting outrage that led to violence and the deaths of almost 80 people in the Oromia region. The killing of a popular singer in Addis Ababa in 2020 also triggered a wave of posts on the social media site, followed by violence in the capital and beyond.

As national elections approach and social media use expands, Hailu said his country is ripe for online disinformation campaigns that could lead to further bloodshed.

“They disseminate ethnic biases, hatred and prejudices so they might instigate conflict in ethnic clashes and political clashes. So, this is of concern to us,” Hailu said.

“We work with partners to flag activity that could potentially thwart participation, exacerbate tensions or contribute to unwarranted perceptions that the voting process or the outcome are illegitimate,” said Michael Baldassaro, senior adviser with the Carter Center’s digital threats monitoring team, a relatively new program in the organization’s global democracy and peace initiatives.

Baldassaro, who spoke to VOA via Skype, said with internet access increasing in many emerging democracies, use of social media is changing the ways candidates and voters interact.

It is also changing how the global nonprofit Carter Center, founded by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, assesses elections.

“We typically do this work in environments that are characterized by deep political polarization where citizens distrust government institutions or election authorities to varying degrees, and their primary sources of media are either unprofessional or hyper-partisan, or both,” Baldassaro explained.

“We find in these environments that people turn to social media, where they find themselves in echo chambers, and encounter bias-confirming content — a good portion of which is false and misleading or demonizes those with different perspectives or beliefs.”

The Carter Center, together with partners in countries where they are monitoring elections, not only flag dangerous online activity, but press tech companies to act.

“If that information is indeed false, we might relate that to Facebook and the human rights policy team or to our counterparts in the country office to take action,” said Baldassaro. “Maybe at that point, they might take action to either downrank or deplatform that content all together. We want to be able to mitigate potential harms in real time.”

Hailu’s Center for Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD) is one of several organizations in Ethiopia monitoring and acting on potential harmful online activity.

“We try to identify those profiles who are repeatedly disseminating false information and demand or advocate for the social media platforms to remove that content as soon as possible,” he said.

In a 2020 report, the United Nations outlined the dangers in Ethiopia of unmoderated content on Facebook. The tech giant said it is increasing content moderation staff in Africa, but Hailu said there are many challenges monitoring and moderating enormous amounts of content in different languages from different locations, including from diaspora communities outside the continent.

“It requires the efforts of multiple organizations and multiple stakeholders,” he told VOA.

With Carter Center support, CARD has expanded its mission beyond Amharic-only language content in Ethiopia.

“We are also now observing at least three local languages,” Hailu said.

But Hailu admits it is still an enormous task monitoring users and content that increases daily, reaching audiences in dozens of different languages or dialects throughout Ethiopia.