KEMMERER, WYOMING — A six-foot-tall plastic Tyrannosaurus rex stands guard outside Robert Bowen’s fossil shop on Pine Street in downtown, Kemmerer, Wyo., in the state’s southwest corner.

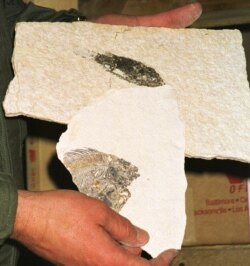

“One of the fun things about some of the fossils is, they tell stories,” Bowen said, pointing to a fossilized stingray hanging on the shop wall. The beautifully preserved disc-shaped skeleton has a chunk missing from its left side.

“He got a little too close to a turtle or an alligator,” he explained. “You can see the elongated bite mark.”

The town of Kemmerer calls itself “Wyoming’s Aquarium in Stone.” Quarries just outside town yield schools of fossilized fish with just a few taps of a chisel. A freshwater lake covered the region 50 million years ago.

The backbone of the town’s economy, however, is a different kind of fossil: fossil fuel. A coal mine feeds the Naughton Power Plant just outside town.

“It’s huge for us, as far as our economy,” said Bowen, who sits on the town council. The plant and the mine provide about 400 jobs and the bulk of the tax base in the town of about 3,000 people.

So it sent a shudder through the community late last year when PacifiCorp, the Naughton plant’s owner, announced that closing the plant early would save its customers nearly $200 million on fuel and maintenance costs.

While coal has powered the industrialized world for centuries, an energy transition is underway around the world. Concern about climate-changing emissions is one factor. But simple economics is pushing coal out of markets it once dominated. The cost of natural gas, wind and solar power have plunged in the last decade or so.

Wyoming reacts

Wyoming has not embraced the energy transition. Environmental arguments for zero-emission wind and solar power don’t get much traction. The state has the nation’s lowest rate of acceptance that humans are the main cause of climate change.

Meanwhile, as markets have changed, the state has not changed with them.

“We’ve been late to the game,” said Robert Godby, director of the University of Wyoming’s Center for Energy Economics and Public Policy. “We have been reticent, or maybe just slow, or maybe we’ve denied the changes that are going on. And so we’ve been slow to react to them. We haven’t been proactive. We’ve been reactive.”

Case in point: A new law puts a wrinkle in PacifiCorp’s plans. It requires the owner of a coal-fired power plant to seek a buyer before it can close the plant. The utility would then have to buy the plant’s electricity back from the new owner.

“We understand that a change is coming, but we’re simply asking that let’s do it with some wisdom,” said State Senator Dan Dockstader, the law’s sponsor. “Let’s not put the plane into a nosedive. Let’s let it glide down easy and sort this out.”

Godby calls it a speed bump.

“If the current owner of a coal fired power plant can’t make money with that plant, why would somebody else buy it?” Godby asked. So far, no buyers have come knocking.

“But on the other side of the coin,” he added, “the devil’s in the details.”

The details are still being written, but Godby said the state may structure the deal so that a new owner can make a profit, despite the fact that PacifiCorp says the plant is uneconomical.

The bill’s main outcome is uncertainty, he added, which companies detest. PacifiCorp may decide to leave Naughton open longer simply to avoid that uncertainty.

Adaptation or extinction

Robert Bowen said the new law will help the town buy time. But he acknowledges that trouble is coming.

“It’s not ‘if,’ it’s ‘when,’” he said. “To prevent some of that, we need to start looking at diversifying our economy here.”

Tourism is one option. Painted wooden signs around town point to the region’s attractions: boating, snowmobiling and, of course, fossils. One sign proclaims Kemmerer the “World Fossil Capital.”

“One of the things that we could be pushing a lot harder is paleo tourism,” Bowen said. The town could do more to promote fossil safaris out to the nearby quarries, where visitors can easily find their own fossils to take home.

Fossil tourism alone won’t save the town, he said, but it would help. The best option would be some kind of manufacturing, he added.

Like the creatures entombed in stone here, Kemmerer must adapt or go extinct.