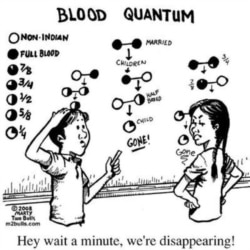

Native Americans have survived centuries of imported diseases, dispossession of lands and forced assimilation. Today, many worry about another existential threat: Blood quantum—a system the U.S. government and many tribes use to measure Native ancestry and eligibility for membership.

Blood quantum (BQ) is based on a simple formula: Half of the combined degree of “Indian blood” an individual’s parents’ possess. So, if both parents have 100% Indian blood, their child will have a BQ of 100%.

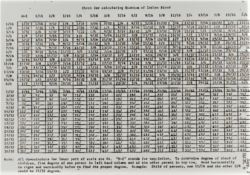

But where bloodlines have been “diluted” by unions with non-Natives, calculating BQ can be complex, as evidenced by a chart published in the 1983 Bureau of Indian Affairs Manual, and percentages are usually expressed as fractions. For example, if a man with one-half BQ marries a woman with one-quarter BQ, their child will have a BQ of three-eighths.

Colonial construct

For thousands of years, Native tribes understood “belonging” in terms of social kinship. Settler colonialism, however, introduced notions of race to determine social status, eligibility to marry, hold office or own land.

By the 19th century, terms such as “mixed-blood” and “half-breed” crept into treaties such as that with the Osage in 1825, by which the United States set aside a separate reservation for “half-breeds.”

Gradually, BQ became the standard test for deciding who was eligible for land and treaty benefits.

In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), touted as an effort to reduce government interference in tribal affairs. The new law, which recognized anyone with “one-half or more Indian blood,” urged federally recognized tribes to form representational governments, draft individual bylaws and constitutions, and decide membership criteria.

More than 260 tribes ended up accepting the IRA and set membership requirements. For some, it was lineal descent from individuals listed on historic “base rolls.” Others mandated BQ of one-quarter or more. A few decided on a combination of lineal descent, residency and/or BQ.

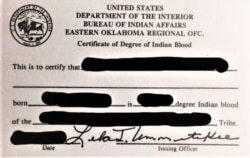

The Bureau of Indian Affairs issues Certificates of Degree of Indian Blood, a form of identification that certifies individuals’ BQ and eligibility for tribal membership.

‘Paper genocide’

But some Native Americans who follow the issue closely say sticking with the BQ system for measuring ancestry is a recipe for disaster.

Jill Doerfler, head of the University of Michigan’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Department, grew up in the White Earth Nation, one of six bands of Anishinaabe (also known as Chippewa) people united under the governing body of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe (MCT).

“What blood quantum does is racialize American Indian identity,” she said. “It is an outside concept used to disenfranchise Native people and tribes from their legal and political status. And it’s the best way to eliminate ongoing treaty obligations.”

Increased urbanization and intermarriage with non-Natives mean bloodlines are diluting, and as time goes on, fewer and fewer individuals will qualify as tribe members and will lose associated health and education benefits.

“And if a nation doesn't have any citizens, there’s no nation,” Doerfler said. “There's no relationship that has to be maintained, and no services that need to be provided. The government could eliminate the whole budget line of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.”

And then, she worries, the government could divest tribes of all their land, resulting in what some term “paper genocide.”

‘Drastic decline’

In 2012, MCT contracted with the Minnesota-based Wilder Foundation to study population trends for MCT as a whole, and its six member bands—White Earth, Mille Lacs, Grand Portage, Fond du Lac and Bois Forte—individually.

“The study showed that if we keep the current one-quarter MCT blood quantum requirement, we will see a pretty drastic decline by the end of the 21st century,” said Mike Chosa, public relations director at the Leech Lake Band.

“In 2013, our population was around 41,000. And in 2098, they predict fewer than 9,000 members,” Chosa said. “And the numbers decline even more rapidly the further you go out.”

Wilder looked at how MCT's tribal population would change over time if different membership criteria were applied—allowing blood from other Chippewa tribes to enter the equation, for example, or reducing BQ requirement to one-eighth.

Wilder concluded that by loosening BQ restrictions, MCT’s population would grow significantly. But for that to happen, MCT would have to rewrite its constitution.

Considering alternatives

In 2018, MCT conducted a tribal survey to gauge interest in doing just that.

“Over half the people were in favor of eliminating blood quantum altogether,” Chosa said. “The other half were in favor of expanding the types of blood that we would consider. In the end, it's got to be an individual decision for all native nations and tribes.”

It isn’t an easy decision, especially for tribes that share casino and other earnings with members. A greater tribal population means smaller per capita payouts.

MCT plans to put the matter to a referendum and, if that passes, a secretarial vote.

Ultimately, however, it will be up to the federal government to decide.

“Unlike some tribes, our constitution was actually written by the Department of Interior and approved by the Department of Interior,” Chosa said. “So, if we want to change it, we need to go through the Department of Interior.”

![Portraits of two Tewa girls from Nambé Pueblo, New Mexico). Published in: The North American Indian / Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.] : Edward S. Curtis, 1907-30.](https://gdb.voanews.com/c2ac4000-3e8a-4c4e-8660-dcadb4934244_w250_r1_s.jpg)