The current U.S. Congress is the most racially and ethnically diverse in history. Nineteen percent of its members are racial minorities, according to the Pew Research Center, but only two Native Americans have seats in the House of Representatives.

Republicans Thomas Cole, a member of the Chickasaw Nation, and Markwayne Mullin, a member of the Cherokee Nation, are from Oklahoma and serve in the House. They are among eight Native Americans who ran in the November 2016 election.

Native Americans and Alaska Natives account for two percent of the total U.S. population, but many analysts believe their representation should be greater, given that the federal government recognizes more than 560 tribes as separate and sovereign governments.

History of exclusion

“Part of the problem is that Native Americans were not granted citizenship until 1924, and it was left to individual states to decide whether “Indians” could vote or not,” said Walter Fleming, who heads Montana State University’s Native American Studies program. ". It wasn’t until after World War II that the last states lifted voting restrictions."

“At the time, the Native population was between 250,000 to 350,000, and so the numbers didn’t allow a whole lot of participation,” Fleming added. “And even after that, there were legal barriers to voting.”

States used various methods to discourage Native Americans from voting, insisting, for example, that voters give up tribal residencies, imposing poll taxes or disqualifying those who couldn’t read or write English.

In some areas, barriers to voting persist.

“Counties have been pretty reluctant to set up polling stations outside of the usual county seats, local schools and courthouses,” said Fleming. “They say it’s because setting up satellite sites is cost-prohibitive; but, of course, that’s just one mechanism for keeping people from voting, particularly in reservation communities where people might not be able to afford gasoline [to drive] to go vote.”

Some states don’t accept tribal cards as legitimate forms of identification - an issue that has become the subject of several lawsuits across the country.

“Native Americans, especially those who live entirely on the reservation, may well have little reason to have things like driver’s licenses,” said Fleming.

Everything to lose

Many Native Americans sense they have little to gain by participating in the political process, observers say. Some refuse to register to vote, recalling a time when being listed on government rolls led to them losing their property or their children to boarding schools and foster homes.

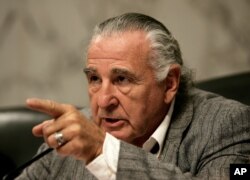

Former U.S. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell recalls conversations with members of the American Indian Movement (AIM), a civil rights and activist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, which promoted greater self-determination among tribes.

“Some of those AIM guys I knew personally,” said Campbell. “And I remember some of them asking me, ‘Why do you want to run for a government that took so much away from us?’"

Campbell, a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe and the first Native American to be elected to the U.S. Senate, said most minority groups, with the exception of those brought to the United States as slaves, came for the opportunities it offered.

“Native Americans are the only ethnic group in America, bar none, who had nothing to win and everything to lose,” he said.

Campbell said he would like to see more Native Americans in Congress, but points to one of the most fundamental challenges. “It’s an uphill battle. There are some congressional races that run into multiple millions of dollars, and Native American people have trouble raising that kind of money.”

Both Fleming and Campbell acknowledge the importance of Native voices, something they say politicians are finally acknowledging.

“Former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle once told me that he didn’t think he could have won the statewide race in South Dakota without the Indian vote,” said Campbell. “If they register and get out to vote, we know there are about five states where they can turn the statewide race.”