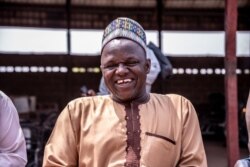

Ayuba Gufwan, father of five, made sure each of his children was immunized against polio at the youngest possible age.

"I was determined to make sure none of my kids got the polio virus," says Gufwan, who was crippled by the disease as a boy. Though a first vaccine dose isn't typically administered before a child reaches two months, Gufwan had nurses vaccinate his children much earlier. He jokingly describes it as "their first meal."

Attitudes such as Gufwan’s propelled Nigeria to a new milestone this week: The West African country has gone three years without documenting a single new case of wild poliovirus. It had at least two cases in 2016, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), though that was down considerably from a 2009 outbreak with 258 cases.

Dr. Usman Adamu, who helps coordinate the Nigerian government's polio eradication operations center, said in a phone interview that the three-year record "is significant in our quest to achieve eradication and, subsequently, certification."

Nigeria could be certified polio-free as soon as mid-2020 if no new cases emerge.

The highly infectious disease remains a threat in Nigeria – Africa’s most populous country – as well as in Afghanistan and Pakistan. It primarily affects children younger than 5, WHO reports, noting that one in 200 infections leads to paralysis and, if breathing muscles are affected, even death.

Authorities hope Nigeria can be declared polio-free as soon as mid-2020.

Nigeria’s government has aggressively pushed a vaccination drive. It’s working with international partners – UNICEF, Rotary International, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the World Bank and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to train health workers and procure the vaccine. Over the last few years, 400,000 people fanned out across the country to spread awareness about polio and administer the vaccine house-to-house.

Raising awareness

Gufwan is part of the awareness campaign, working to ensure that others avoid his experience.

At age 5, he contracted the virus and lost the use of his legs, forcing him to crawl about his home in a village incentral Nigeria'sPlateau State. Polio kept him out of school for much of his youth. At 19, an uncle made him a hand-pedaled tricycle and he went on to study law at a university. Now he's a popular advocate for people with polio.

His charity organization, Wheelchairs for Nigeria, has supplied more than 26,000 locally produced tricycle-type wheelchairs for Nigerians living with the disease.

Gufwan and others campaigning for better awareness about polio have had to dispel cultural and religious misconceptions about the polio vaccine, particularly in northern Nigeria, where Islam is the dominant religion.

In the region's lingua franca, Hausa, polio is translated asshan innah. This conveys the idea that evil spirits are paralyzing a child's legs, leaving the child with polio's telltale symptom, floppy limbs.

Hostility toward the vaccine also came from respected Muslim leaders and scholars in Nigeria.

“Some fundamentalist Muslims rejected the polio vaccine and came up with this conspiracy theory that the vaccine had been adulterated and that it had the potential to sterilize – particularly the girl child,” Gufwan said. They contended vaccination “was a calculated attempt by the Western powers to reduce the Muslim in Nigeria and other parts of the Islamic world.”

Those suspicions were partly grounded in a 1996 episode in which the U.S. pharmaceutical company Pfizer set up trials in northern Nigeria for a new meningitis drug. Hundreds of children were given the drug and suffered severe side effects. Many parents said they were not told that their kids were being used to test the medication.

Another rumor was that the vaccine contained monkey parts; some Muslims consider it taboo to eat the animal. A hostile backlash led to the vaccination campaign's suspension in parts of the country in 2003. And that led to a spike in new cases.

Suspicions intensified again in 2011 among Nigerian Muslims after news broke that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had set up a fake polio vaccination drive to track down and kill al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden at his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

Changing perceptions

It took the help of local Islamic leaders to squelch the rumors swirling in northern Nigeria.

Alhaji Samaila Muhammad Mera, emir of Argungu in Nigeria's Kebbi State, has used his role as a traditional ruler to spread awareness of polio and vaccines.

“To change perceptions, to change attitudes, you need to get a messenger that is trusted by the community,” he explains.

He began by making a public show of getting his children vaccinated. His state hasn't had a new case of polio in five years, and a drastic change from the 15 cases in 2009.

Two other issues complicate Nigeria’s quest for a polio-free future: insecurity and poor sanitation.

The Boko Haram terrorist group’s ongoing attacks against villagers and Nigerian troops have made it nearly impossible to reach certain areas in the country’s northeast. In 2013, suspected Boko Haram gunmen killed nine polio workers. Today, the Nigerian government, using satellite imagery and local population data, estimates about 60,000 children have not been vaccinated.

Sanitation is an issue because polio usually spreads through contact with the feces of an infected person. With many homes lacking toilets, almost a fourth of Nigerians practice open defecation, UNICEF and other authorities estimate. Nigeria’s government and international partners have been campaigning against the practice, building millions of toilets since 2014.

Gufwan calls it "very, very shameful" that Nigeria is the only African country yet to be polio-free but hopes it will soon be. "As they say, better late than never."