On Monday, March 11, the court in Amsterdam began looking into the appeal submitted in March 2017 by representatives of four museums in Crimea claiming their rights to a collection of Scythian gold artifacts that was lent to a Dutch museum in February 2014, one month before Russia annexed the Black Sea peninsula from Ukraine.

The RFE/RL reported that the claimants in the case – the “Crimean museums” are not participating in the court hearing.

On March 11, the first day of hearing in the Dutch capitol the “Crimean museums” published a statement on a Website of the Eastern-Crimean Historical and Cultural Museum-Preserve organization that is part of the Russian Ministry of Culture.

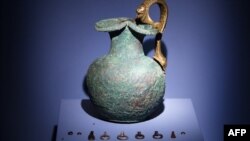

It said that the “unique collection” forming the “Crimea – the Golden Island in the Black Sea” exhibit is “important not only for the museums but for all of the Crimean people as well.” The statement added the 2,111 items, including jewelry and a fourth-century helmet, should not be “torn away from their history, context and collections for political reasons.”

There are “no legal, cultural or historical reasons” to grant Kyiv the items, the statement added.

Ukraine said its claim over the Scythian gold collection is based on legal provisions of the 1972 UNESCO Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, which says the property rights belong to the states on which territory the treasures are situated.

Kyiv also argues the collective “Crimean museums” are legally "inappropriate claimants" in the European country’s court since they operate on the basis of the Russian law and as representatives of the Russian state, which EU views as an occupying power in Crimea.

In December 2016, a Dutch court ruled that the items should be returned to Ukraine, arguing that only sovereign countries can claim objects as cultural heritage.

“Ownership questions have to be settled when they have been returned to the state and in accordance with the law of the state in question,” Reuters quoted Judge Mieke Dudok van Heel as saying. “The Allard Pierson Museum [in Amsterdam] must return the treasures to Kiev.”

Russian Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky told Russian state media at the time that the decision would set a “dangerous precedent,” and he threatened to cut off museum exchanges with the Netherlands if it was upheld.

“We are talking about an unprecedented alienation of museum values. This can only be compared to lootings dating back to Napoleon’s Italian campaigns, or to those during the times of Nazi aggression. I think that the Dutch court ruling was absolutely politicized. It destroys the very system of exhibition exchange,” RT quoted Medinsky as saying.

Ukrainian authorities welcomed the December 2016 decision, with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin saying: “The Scythian gold is coming back home - to Ukraine. I’m sure, it will also return to Ukrainian Crimea.”

The four Crimean museums – the Central Museum of Tavrida, Kerch Historical and Cultural Preserve, Bakhchysarai Historical and Cultural Preserve and Chersonesus Historical and Cultural Preserve – were given three months to appeal the decision, which they did on March 28, 2017.

Russia’s TASS state media outlet says a court spokesman told the agency the Amsterdam Court of Appeals would deliver a verdict in the Scythian gold case on June 11, 2019.

The international community, by and large, does not recognize Crimea as Russian territory, and a March 2014 United Nations General Assembly vote backed Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

Elena Gagarina, director of the Kremlin Museum in Moscow, said in December 2016 that she understood the Dutch court’s decision.

“In this case, when these objects were taken from the territory of Ukraine and belonged to Ukraine as a state, this decision seems perfectly reasonable to me,” Reuters quoted her as telling Russia’s Interfax news agency.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture first agreed to transfer the collection, at that time under the auspices of the State Museum Fund of Ukraine.

The Director of the Central Museum of Tavrida, Andrei Mal’gin, has argued that the Scythian artifacts are fundamentally under Crimean, and not Ukrainian, dominion.

The items were excavated in Crimea, and funding for the excavation came from the local budget, not the central one, Mal’gin told the Russian-language Ukrainian newspaper Segodnya. He added that he believed the outcome would depend on the “political situation.”

But Lyudmila Strokovich, head of the Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine, told Segodnya the Crimean museums, which “immediately recognized themselves as Russian,” did not coordinate with Kyiv when extending the contract governing the loan of the items to the Dutch museum. This, in her words, meant that after June 13, 2014, the exhibits had the status of having been “illegally exported from Ukraine.”

Ralph Oman, a lecturer in intellectual property and patent law at the George Washington University Law School, told Polygraph.info that the World Intellectual Property Organization in Geneva is working on a new treaty that could protect folkloric treasures, including the Scythian gold.

Such a treaty would provide protection for “an undetermined number of years,” but it “has not yet been finalized or ratified,” Oman said.

Oman said the Scythian gold case is analogous to “former colonies and materials being sent back to British museums,” although that line of reasoning is likely a dead end for the Crimean museums.

“It’s perhaps a good moral argument [for returning the artifacts to Crimea], but not a strong legal one,” he said.

Oman said the possibility the appellate court could uphold the lower court’s decision was “strong,” adding that “to decide otherwise would be going out on a limb.”

Given the highly complicated and precedential nature of the case, which remains under appeal, Polygraph.info finds that the museums’ claim that there are “no legal, cultural or historical reasons to hand these items over to Kyiv” remains unclear.