On February 1, the Tatmadaw (or armed forces) of Myanmar staged what Western leaders are calling a military coup, detaining National League for Democracy Party (NLD) leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other democratically elected leaders.

The Tatmadaw declared a nationwide state of emergency, with Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing assuming power.

On February 3, Suu Kyi was charged with violating import-export laws for allegedly possessing handheld radios brought into the country illegally. Police are seeking to hold her until February 15.

The same day, the NLD said their offices across the country had been raided.

The military claims its power grab is constitutional, arguing that allegations of fraud in the November 2020 elections were not sufficiently addressed.

In those elections, the NLD roundly defeated the military’s proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). The NLD, which captured 83% of available seats, calls the fraud allegations unfounded, and outside observers largely agree.

The November poll was only Myanmar’s second election since half a century of military rule ended in 2011.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres “strongly” condemned the detention of Suu Kyi, President U Win Myint and other political leaders. Guterres expressed “grave concern regarding the declaration of the transfer of all legislative, executive and judicial powers to the military,” saying the move “represent a serious blow to democratic reforms in Myanmar.”

Various world leaders also condemned the power grab, including U.S. President Joe Biden, who threatened sanctions.

Neighboring China has neither condemned nor supported the action.

However, on February 3, China blocked a UN Security Council resolution condemning the coup.

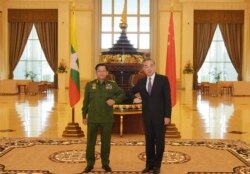

Moreover, weeks prior to the military takeover, China’s top diplomat met with Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing.

In that meeting, according to Reuters, Min Aung Hlaing reportedly said the army was prepared to act over the fraud allegations, with China signaling its continued support despite the threat of new Western sanctions.

The Global Times, the Chinese Communist Party's daily newspaper, said that Beijing had maintained good relations with both Myanmar’s civilian government and the military, expressing its desire for the two sides to reach a compromise through negotiations.

The newspaper also cited experts as saying Myanmar should be wary of “external interference.”

Yin Yihang, a scholar from the Beijing-based think tank Taihe Institute, told the Global Times that “U.S. civil rights groups have maintained a presence in northern Myanmar, radicalizing local people.”

"As per the current situation, the U.S. may also adopt a 'color revolution' approach to Myanmar," Yin said.

The claim that U.S. civil rights groups have “radicalized local people” in northern Myanmar is false.

In fact, the U.S. presence in the region is minimal, while Beijing’s own involvement in northern Myanmar is unmatched by any other state actor, despite Chinese claims of noninterference.

Yin’s mention of “northern Myanmar” was a reference to Kachin state and Shan state, which have seen decades of ethnic conflict and the world’s longest-running civil war. Both states share a border with China.

The United States Institute of Peace stated in a September 2018 report: “Beijing supports the Myanmar government and its peace process, but at the same time provides shelter, weapons, and other assistance to some of the ethnic armed organizations.”

In 2011, hostilities in Kachin state reignited between government forces and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) following a 17-year ceasefire.

According to some observers, Chinese infrastructure projects seen as strategically important to both sides have been a catalyst for renewed hostilities.

The conflict at times has spilled over into China. Although Beijing has played a role in mediating the conflict, it has also provided advanced weaponry to rebel forces, including surface to air missiles.

The KIA has sought international mediation, including from the U.K., UN and U.S. But China has rejected the so-called “internationalization of the Kachin issue,” opposing Washington’s involvement in an area close to China’s border on national security grounds.

In 2016, China’s ambassador to Myanmar asked his U.S. counterpart not to travel to Kachin or eastern parts of Shan states, saying the United States “should respect China’s interests.”

With Beijing’s concerns as a backdrop, the U.S. has played a very limited observer role in resolving the conflicts in Myanmar.

In Myanmar’s Shan state, hostilities flared up in January 2018 and intensified in December 2020. China maintains strong ties with the United Wa State Army (UWSA), which operates within the Wa Self-Administered Division in the eastern part of Shan state.

The USWA continues to play a central role in the conflict in northern Myanmar despite signing a bilateral ceasefire with the Myanmar government in 1989. Anthony Davis of the Asia Times referred to the USWA as the “godfather of the so-called Brotherhood Alliance of northern rebel factions.”

In November 2019, Davis reported that China had possibly lifted an “embargo” on supplying its rebel allies with portable air defense systems to help push the Tatmadaw into a ceasefire with the Brotherhood Alliance.

While there is no evidence Beijing officially supports the trafficking of natural resources or war profiteering in Kachin and Shan states, Chinese entities, including retired People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers, have reportedly profited through sustaining civil war and instability there.

By contrast, accusations that U.S. civil groups or governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are radicalizing people in the region appear to be fabricated.

According to ACAPS, a nonprofit humanitarian needs assessment and analysis group, “[a]ccess restrictions for humanitarian organizations and active conflict have eroded the coping capacity of communities in Kachin and Shan [states].”

Local, national and international aid organizations have expressed concern over aid restrictions and called for greater access to humanitarian aid in the region.

The Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU), which tracks the humanitarian and development community in Myanmar, noted that 73 agencies had reported activities in Kachin state as of August 2020.

Of those, 50 agencies were engaged in development-focused projects, 17 were supporting vulnerable groups not related to internally displaced persons (IDPs), 29 were engaged in activities supporting IDPs and host communities, and 23 were engaged in other IDP-focused activities.

Most of those activities were carried out by international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) or UN agencies.

A majority of projects targeting non-IDPs were health-related, including HIV/AIDs treatment/prevention and reproductive health programs.

Other projects centered on promoting gender equality, strengthening civil society, providing microfinance and vocational training, and other peace-building initiatives.

Approximately 102 agencies reported activities in Shan state. Of those, 57 were INGOs, 20 were national NGOs or community organizations, and 14 were UN agencies.

Their projects largely covered health, civil society, agriculture, education, protection and peace building/conflict prevention.

According to the State Department, “U.S. development assistance [in Myanmar] focuses on deepening and sustaining key political and economic reforms, ensuring that the democratic transition benefits everyday people, and mitigating division and conflict.”

The U.S. has also worked to enhance food security and disease prevention in the country.

In 2012, the U.S. re-established a U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) mission in Myanmar.

In its 2019 Fiscal Year, USAID’s Office of Food for Peace (FFP) gave more than $22 million to the United Nations World Food Program to provide “food assistance and cash transfers for food to more than 326,000 food-insecure people in Kachin, Rakhin, and Shan States.”

FFP also supports the UN Children’s Fund and UK-based Save the Children global charity.

USAID is also involved in civil society, conflict resolution, public health and education initiatives in Myanmar.

Other U.S.-funded groups providing aid to the country, if not northern Myanmar, include the U.S. Departments of State, Commerce, Energy, Labor, Health and Human Services, Justice, Defense, and Treasury; the U.S. Peace Corps, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the DEA, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the Fish and Wildlife Service.