With the NATO’s month-long Trident Juncture 18 exercise kicking off last week, Russian media have tried to paint the war games, involving 50,000 troops from 31 countries, as an act of aggression.

Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu said: “NATO’s military activities near our borders have reached the highest level since the Cold War times,” adding the drills were intended to simulate “offensive military action.”

Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said such “irresponsible actions will inevitably destabilize the military and political situation in the north,” adding Russia would take “necessary tit-for-tat measures to ensure its own security."

NATO said the drills are not an act of aggression, adding Russia had been invited to observe them.

Trident Juncture 18 comes one month after Russia carried out its Vostok military exercises, to which China, Mongolia and NATO-member Turkey were invited. Regarded as the largest Russian-led military exercise since 1981, some 297,000 service personnel took part in that drill.

On October 29, RT’s Murad Gazdiev said that the simulated enemy in the latest NATO drill is “unsurprisingly exactly as powerful as Moscow,” adding both sides have been “going to extremes staging bigger and bigger wargames.”

The report cited NATO spokesman Dylan White, who said Vostok demonstrates Russia’s focus on exercises simulating a large-scale conflict, which “fits into a pattern we have seen over some time – a more assertive Russia significantly increasing its defense budget and its military presence.”

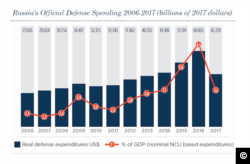

Gazdiev found fault with this claim, saying that “Russia’s military budget has been decreasing, not increasing, year after year,” and noting that Russia’s defense spending has shrunk from $69.2 billion in 2016 to $46 billion in 2018. NATO’s spending during that period, by contrast, grew from $924 billion to $1.103 trillion.

He said that in spending terms there is no competition between NATO and Russia, adding it has led to a remarkable cycle, whereby NATO ramps up its fighting machine, “forcing” Moscow to respond with its own buildup “which NATO then calls Russian aggression,” which the alliance then uses “to justify stationing more tanks and more troops near Russia.”

Gazdiev’s report concluded with a rhetorical attempt at dismay, asking how much longer the situation can escalate before a spark is put to “this trillion dollar powder keg.”

Russia’s ‘Shrinking’ Defense Spending Explained

On the surface, the basic point is true: NATO’s defense spending has increased from 2016-18, while Russia’s has declined.

But the 2017 cut was the first drop in Russian military spending since 1998.

Ultimately, the situation is much more complicated than simply inferring intent from outlays. But first, the reasons behind those cuts warrant consideration.

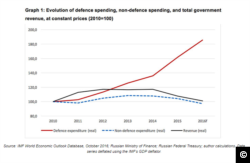

As noted by several analysts, Russia’s 2016 defense spending was inflated by “a one-off adjustment” to pay off debt that had accumulated over the years.

That year, the Finance Ministry reportedly provided 792 billion rubles (approximately $12.03 billion at today’s exchange rate) to help pay off defense contractors. Another 186 billion rubles ($2.82 billion dollars) was spent to that end in 2017, making outlays for those years appear higher, wrote Michael Kofman, a senior research scientist with the CNA Corporation.

Kofman said a tightening in funding controls had also disrupted “the continuity of Russian defense-spending data.” Previously the industry had been allowed to hoard advances for armaments that had not been produced as scheduled.

He also noted it was analytically unhelpful to measure Russia’s defense budget in dollars, as “Russia’s defense sector doesn’t buy much of anything in dollars,” resulting in purchasing parity distortions.

Another factor concerns the fact that Russian Federal Treasury data only accounts for actual expenditures, not full allocations, wrote Mark Galeotti, a senior non-resident fellow at the Institute of International Relations Prague.

Then there is the issue of transparency. Galeotti says that in Russia, “even more so than in the West,” defense and security expenditures “often appear under different budget lines and obscure headings.”

“Pre-conscription physical and skills training is outsourced to schools through the revived GTO (Ready for Labor and Defense) program,” Galeotti wrote. “The cost for this comes out of the education budget, while part of the aid and development budget is likely paying for the mercenaries fighting in Syria.”

Olga Oliker, a senior adviser and director of the Russia and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), mirrored that point. Oliker said different components of Russia’s defense budget have been classified at different times, making them unavailable for analysis. Russia is also not unique in funding some defense-related items, like portions of its nuclear weapons program or military pensions, through sources other than its defense budget.

That, coupled with the fact that civil defense and paramilitary forces are left out of the budgetary equation, further muddies the funding waters. Underlining that point is evidence that Russian mercenaries with opaque funding sources have been linked to what would normally be regular military operations, including sometimes combat, in eastern Ukraine, Syria and the Central African Republic.

“This makes year-on-year comparisons a challenge, and comparisons with other countries all the more so,” Oliker said.

Then there is the issue of force size and how it relates to the relative cost of living. As noted by Oliker, “maintaining a military force of 500,000 high-quality personnel in a country with lower salaries is obviously cheaper.”

For example, in January it was announced that pay hikes would see a Russian lieutenant now earning 66,100 rubles ($1,006) a month. By contrast, a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army earns between $3,496 and $4,839 per month. Higher related outlays will further be seen in military housing, food service medical care and bonuses.

Galeotti said that that any windfalls from rising oil prices, for example, always have the potential of resulting in specially-mandated military allocations.

Even so, from the high-end estimate of 25.5% to a notional cut of 5%, Russia’s military spending did drop between 2016-17. The question is why.

The narrative Russia is presenting -- that defense spending cuts are part of some natural desire for the Kremlin to scale back its military operations just as it is embarking on a 10-year force modernization plan -- appears counterintuitive.

Rather, a drop in oil prices, Western sanctions related to Russia’s military actions in Ukraine and related economic woes, are often cited as the main impetus behind the cuts.

Siemon Wezeman, a senior researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, which carried out a study on Russia’s defense cuts, said that in a time of austerity, the military was not the first thing to be cut.

"The military budget has been restricted by economic problems that the country has experienced since 2014," Wezeman told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, adding that Moscow first implemented infrastructure and education cuts until there was finally no choice but to "spread the pain."

The other question is whether there really is “no comparison” between Russia and NATO because of the budgetary disparity.

Leonid Bershidsky has argued that, nuclear parity notwithstanding, Russia is much better at getting more bang for its buck when it comes to projecting military force in the modern era.

“Today's wars aren't fought with fat wads of money,” Bershidsky wrote. “The adversaries are mostly small, agile forces that aren't as well-resourced as nation states. Fighting them requires a combination of local knowledge, brute force applied only at important points in a conflict and ability to shift risks onto the shoulders of irregular fighters. Russia kept cutting its defense budget all through its participation in the Syrian war. Yabloko, an opposition party, earlier this year put the cost of the Syrian operation for Russia at about 140.4 billion rubles ($2.4 billion at the current exchange rate) since September, 2015; that's some 4% of what the U.S. allocated to overseas contingency operations in 2017 alone – and the outcome is as good as Russia could have expected.”

Simply put, Russia has proven adept at making due with less.

Ultimately, Russia’s de facto annexation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, its outright annexation of Crimea, its ongoing occupation of Moldova's breakaway Transnistria region and its clandestine war in eastern Ukraine belie the claim that Russia itself is the victim of aggression by its neighbors.

So while it’s true that Russia’s military spending has taken a temporary dip, that in itself does not demonstrate a desire for peace with its neighbors.

And so we find RT’s report in this case is at best misleading.