Nestled amid the snow-capped peaks and pristine valleys of Kashmir, work is nearing completion on the Udhampur-Srinagar-Baramulla Rail Link (USBRL), an ambitious undertaking set to connect the picturesque region to the rest of India. The rail line is expected to revolutionize transportation and connectivity in the region.

With a length of 272 kilometers, the rail line will provide a crucial link between the Baramulla district in Indian-administered Kashmir and the outside world, allowing rapid movement of people, goods and security personnel.

Featuring dozens of tunnels and what is billed as the world’s highest railway bridge, the line is an engineering marvel. But it also provides India with a vital strategic asset, easing access to a restive region bordered by India’s two most important rivals, Pakistan and China.

Besides providing relief to the people, the railway network is also of strategic importance from the security point of view, especially in a place like Kashmir, said Darshana Jardosh, India’s minister of state for railways, during a visit to inspect progress on the line.

Geological surprises

Since the beginning of the last century, more than half a dozen attempts have failed to carve a rail route through the rugged mountain range that isolates the Kashmir Valley.

The path is riddled with geological surprises and countless challenges, making it perhaps the most difficult railway building effort in the Indian subcontinent.

Running from Udhampur, 33 kilometers northeast of Jammu, to Baramulla in the Kashmir Valley, 42 kilometers northwest of Srinigar, the project includes the construction of 38 tunnels with a combined length of 119 kilometers, according to Prabhat Kashyap, the quality control project head at Afcons Infrastructure Ltd. These include the tunnel between Sumber and Arpinchala stations and the Pir Panjal Tunnel, the longest transportation tunnel in India at 12.75 and 11.2 kilometers, respectively.

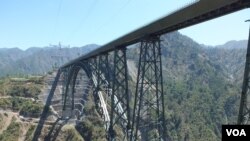

There are also 931 bridges spanning a combined length of 13 kilometers, including the iconic Chenab Rail Bridge, claimed to be the world’s highest railway bridge, and the Anji Khad Bridge, Indian Railway’s first cable-stayed rail bridge.

Irfan Mushtaq, a contractor for Konkan Railways, is building a railway station at Reasi, near the southern end of the line. He told VOA that it has been one of the most challenging projects he has ever undertaken, given the terrain, unavailability of skilled labor and inclement weather.

“We have worked day and night for this project to complete. This project will benefit the locals of Reasi and the people of the region as a whole,” he said.

'Remarkable feats of engineering'

The USBRL was declared a “national project” in 2002 and is considered one of the most challenging tasks undertaken by Indian Railways since India’s independence in 1947.

According to Kashyap at Afcons, the USBRL project showcases “remarkable feats of engineering in overcoming challenging terrain and environmental considerations while promoting sustainable and modern rail transportation in the region.”

The Hindustan Construction Company has worked for Indian Railways on many projects, including the Pir Panjal Tunnel. HCC is building the Anji Khad Bridge across the deep gorges of the Anji Khad River, a tributary of the Chenab River.

Project manager Ajay Kumar Pashine told VOA that the 750-meter bridge, including an asymmetrical cable-stayed section stretching 473 meters, is one of the most challenging aspects of the overall project.

Rail connections have played a role in the region since 1890, when Maharaja Pratap Singh, ruler of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, built a line that ran westward from Jammu to Wazirabad Junction in what is now Pakistan.

Service on the line was discontinued after the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, and the once-thriving rail link fell into complete disuse.

India established a rail connection to Jammu after gaining independence from British rule, with the first passenger train arriving at Jammu station in December 1972. But it has taken another 50 years for Indian Railways to surmount the problems of pushing the rail line through to the Kashmir Valley.

Y.R. Gupta, a former station superintendent with Northern Railways, recalled the 1971 ceremony accompanying the arrival at Jammu station of the first passenger train, nicknamed the Srinagar Express.

“The project was a remarkable feat of continuous progress, even during the Indo-Pak War of 1971, making it an unforgettable chapter in world history,” Gupta said.

Boost to tourism

Devendra Sharma, a site engineer whose company, Afcons Infrastructure Ltd., has been building a bridge at Reasi since 2016, lauded the employment opportunities created by the project and the expected contribution to the region’s overall economic development.

“On average, we employed 700-800 laborers daily to complete this bridge, which we expect to complete by the end of May,” he said. “We have employed locals as well to take them on board.”

The railway line will also boost tourism in the region, with travelers being able to soak in the beauty of the Kashmir Valley by train. And the valley’s farmers will enjoy greater access to outside markets, freed from their reliance on roads that are slow and subject to frequent disruptions because of landslides and other issues.

For some Kashmiris, hopes for an economic boom are tempered by fears that the line will bring unwelcome changes. Locals see several government measures proposed since Jammu and Kashmir was stripped of its autonomous status in 2019 as part of a bid to transform India’s only Muslim-dominated region into one with a Hindu majority.

“The rail link could alter the demographics of the region and dilute the Kashmiri identity,” said Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, a local resident in his late 60s. “Also, it could increase security forces in the region, leading to further militarization of the valley.”