In an effort to control militancy and the alleged abuse of madrassas (religious seminaries) by some militant groups operating in the country, Pakistan’s government recently announced plans to bring all madrassas under the formal education structure of the country.

Ahsan Iqbal, Pakistan’s interior minister, reportedly told a seminar last month the government already has allocated funds for initiating the reforms in the country’s education sector, and they include modernizing the educational curriculum and bringing traditional seminaries into the formal government structure.

The new measures are part of efforts to prevent the abuse of religious schools in the hands of militant groups.

Of the four provinces of the country, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa seems to suffer more than the others from the problem of madrassas being abused by militant groups, according to officials.

A 2015 report by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial government called 145 religious schools in the province “highly sensitive” and noted that 26 percent of madrassas in the province remained unregistered and off the official books.

Officials charge the problem still exists, and the government plans to address it.

“Unfortunately, some madrassas in the terror-wrecked KP [Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] had been involved in promoting extreme ideologies in the past decades and some even have worked as facilitators and sympathizers for terror groups,” Sardar Yousaf, Pakistan’s federal minster for religious affairs, told VOA.

“By mainstreaming the madrassas, the government will ensure that no one is allowed to promote extremist ideologies, terrorism, hatred or sectarianism. We cannot allow it at any cost,” Yousaf added.

Yousaf said the planned reforms would be implemented across the country in all madrassas, but the government has not yet set any deadline for provinces to meet.

“All provinces are required to implement the madrassa reforms. Sindh, Baluchistan and Punjab are also working on plans to implement these reforms in their provinces at their own pace,” he said.

National Action Plan

Pakistan’s interior ministry last year directed all provinces to devise strategies and mechanisms to place madrassas under the national educational system in an effort to comply with the National Action Plan (NAP), a 20-point national strategy adopted in 2015 to counter terrorism in the country.

Yousaf said the registration of madrassas and efforts to bring them into the mainstream educational system are all part of the NAP.

“The initiative shows our effort and commitment to implement the National Action Plan that clearly states religious schools should be regulated and monitored by the government,” Yousaf said.

Some analysts applaud the government’s recent efforts, but point to past failed attempts.

Rahimullah Yousafzai, a Peshawar-based journalist, pointed toward the failed madrassa reform project initiated by former President Pervez Musharraf in 2002.

“There had been attempts to bring reforms to the madrassa system in the past as well, but there was no success. Remember what happened to the madrassa reforms program initiated by Musharraf?” Yousafzai asked.

Yousafzai said change has to be participatory in nature and must involve religious scholars in order for it to succeed.

“In order to achieve long-lasting results and to bring revolution in the madrassa education system, the government will have to get full consent of the religious scholars belonging to different sects of Islam,” Yousafzai said.

Yousaf asserted that problem has been ironed out this time around and the planned reforms have the blessing of religious leaders across the country.

“We’ve got phenomenal response from the religious clerics and scholars representing different madrassas across the country. They're willing to introduce the reforms in their religious seminaries,” Yousaf said.

According to Pakistan’s Board of Madrassas, there are about 2.5 million students enrolled in more than 3,500 registered madrassas across the country.

Additionally, there are thousands of unregistered madrassas for which the government has no exact count.

Resistance to science

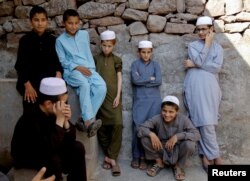

Madrassas, for the most part, follow a curriculum that’s heavily dependent on Islamic theology and the Arabic language. There seems to be resistance from religious clerics to the introduction of scientific subjects. Some experts are hopeful the government will modernize the system and allow millions of children access to science and other necessary subjects.

“These are much-needed and long-awaited reforms. It is time to introduce modern academic tools to the enormous and unregulated madrassa network, which houses millions of children across the country,” Yousafzai said.

Some madrassas in Pakistan have been accused of links with terror groups and promoting hatred and intolerance.

For instance, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-based Darul Uloom Haqqania, a madrassa with thousands of students, is believed to have sympathy for the Afghan Taliban fighting the U.S. and Afghan forces in Afghanistan. The Islamic seminary is often called the “University of Jihad” by critics inside and outside Pakistan.

“There is evidence that many Islamic seminaries in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa openly participated in militancy in the past and some even worked as promoters and recruiters for terror groups, such as Taliban fighting in Afghanistan,” Hasan Askari Rizvi, a regional analyst from Lahore, told VOA.

Rizvi said the number of madrassas in Pakistan grew over the years partly because of a lack of formal education in poor neighborhoods and the government’s negligence.

“The government is responsible for the deteriorating social, educational and financial setup of the religious seminaries. It was because of government’s negligence that some madrassas promoted extreme and ultraorthodox ideologies and continued to impose a hard-core interpretation of Islam,” Rizvi said

Rizvi noted that religious schools in Pakistan are a good alternative for people because they promise food, shelter and education, and attract a large number of students, mostly from the impoverished classes of society.