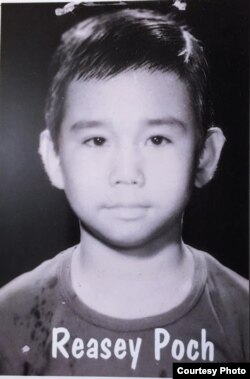

Father's Day. On this day every year, I stare at the black and white identification photo of my father and try to remember the details of the last time I saw him.

It was in Cambodia, on a September morning in 1977. I was 9 years old. At the time, I was living with my grandparents, mom and two sisters in a remote village of Kampot province, about 50 kilometers from the Vietnamese border. It had rained all night, and I was in our tiny hut alone. I couldn't remember where everyone was, but when I woke up, I saw someone I did not expect: my pale-looking father who was in his early 40s.

We were living under the Khmer Rouge regime. It was a communist regime that was responsible for the death of approximately 1.7 million people who died of starvation, forced labor and extrajudicial killings.

My father was away at a remote labor camp where all the men lived and worked together. They could only come home a few times a year on a few occasions, like the Khmer New Year. But it was September. There were no holidays that I knew of.

"I came home late last night. You were asleep and I didn't want to wake you up," said my father as he stared at our leaking roof made of straw.

It turned out that his mobile unit was needed at another village where a bridge had collapsed due to the heavy monsoon rains. He could come home to sleep for a few hours before taking off again.

I was glad to see my father that morning. I was glad to see that he looked healthy although skinny. But I did not express my happiness in words. I didn't even hug him. Partly, it's my upbringing. We never hugged. I don't remember ever having close physical contact with him.

Then he pulled out something from the leaky roof. It was a small yellowish plastic bag that looked like it had been exposed to the sun and heat for a long time. He unwrapped it and pulled out a small piece of white paper. It was a small black and white ID photo that had some dried glue on the back. It was my father's ID photo. I did not know he had kept it for over two years!

"Keep this picture. Hide it well. And when you see your sister Chenda, give it to her," he told me.

I just took it from his hand and nodded. I wondered why he would take it out and give it to me and tell me to give it to my elder sister. But I did not dare to ask him.

"I have to go to the dining hall to find out what time we are leaving. I will see you in a bit," he said.

About an hour later, my father returned. "I have to go. But I want you to follow me. Don't follow me too close. Don't let anyone know or see you are following me. If you see them tie my hands behind me, it means that you are not going to see me again." He said it without expressing any emotions.

"Bart, bart," I said in Khmer. It means "yes, yes" without any emotions as well. For the past two years, people had been taken away. They were told it was the order from above. No questions were allowed. You just had to leave with the people in black pajamas, sometimes at night. Those people who had been taken never came back.

But those were individuals. My father left with his whole mobile unit that consisted of about 40 men. So, it should be OK, I thought. They were only needed to help rebuild a bridge, and then they would return. My father worried for nothing, I thought.

"I am going now. Please remember not to fight with your sisters. Love one another. And don't give your mom a hard time, OK?" my father said. Again, he sounded like he was not coming back. Again, I just nodded my head and said, "Bart, bart."

When my father left with a few other men near our huts, I quietly followed them. I walked far enough behind them so they did not see me but close enough so I wouldn't lose them. The bushes along the trail allowed me to follow my father quite easily.

About 15 minutes later, my father walked into a house along National Road 3, which connects Phnom Penh to the southeastern province of Kampot.

I walked back and made a short cut to the road. I climbed and hid in one of the mango trees that were planted along the road. From the tree, I could see what was happening. It was far enough that no one from that house could see me. And even if someone saw me, they wouldn't suspect that I was watching. I could be just someone who climbed the mango tree for fun.

Nothing happened for a while. About 15 minutes later, people started emerging from the house. They came out one by one with their hands tied behind their backs. Two soldiers with AK-47 rifles motioned them to go into an army truck that was parked nearby. They hurriedly walked up a wooden board that leaned into the back of the truck – a military truck that the U.S. had donated to the previous government.

My heart was beating so hard I thought it would jump out of my chest. I started to sob uncontrollably. My father had predicted it all along. That's why he gave me his photo that he had hidden for over two years in our thatched roof. That's why he told me to follow him. That's why he told me that if they tied his hands behind his back, he wouldn't come back. That's why he told me to love my sisters. And that's why he told me to listen to my mother.

The truck passed me. It was heading south on the National Road toward Kampot City. Everyone was squatting with their heads down, so when the truck passed me at a fairly fast speed, there was no way I could identify my father.

After the truck had passed, I remained in the mango tree and continued to cry. I felt weak, tired and short of breath. But I still had hopes. I told myself that my father was wrong despite what I had just seen. I still hoped that they would put my father and the men in his group in a jail or another hard labor camp and spare their lives. I still hoped that one day I would see my father again.

I don't remember how I broke the news to my mother when I saw her after that night. I don't remember how she reacted. I can't fathom how she must have felt after the deaths of two young children and then her husband. I never told my two sisters. It was too painful.

I somehow managed to keep my father's photograph safe and eventually did as my father told me, giving it to my sister in April 1978, during the Khmer New Year celebrations. My grandmother helped me hide it inside my blanket. She created a small pocket at one corner of the blanket and placed the photo in there. Today, my two sisters and I each have a framed copy of that precious photograph. Our children know what their grandfather looks like.

When I started working as a broadcaster at VOA Khmer in 1993, I was hoping that my father was still alive and would hear my voice on the shortwave radio. I imagined he would somehow contact me, and I would see him again. A year went by. Two years went by. My dream of seeing my father again became dimmer and dimmer, like a burnt candle. By the third year, I realized I needed to accept the fact that he had gone.

It has been 46 years since my father was taken away, but it seems like it happened just yesterday. I remember what my father told me on that fateful day. But his words were just like words on a transcript. There are no sounds or emotion. I do not know the fate of my father in the hands of those Khmer Rouge soldiers. I do not know if they put him in a prison, as I had hoped, or if they killed him.

If they killed him, I do not know how they carried it out. Was it a gunshot to the head? Was it a firing squad? Or was it a blow to the head with some sort of object? What did they claim he was guilty of? What crimes did they say he might have committed? Where and when was his trial? What was the evidence? Who found him guilty? Were the allegations serious enough that he would have deserved a death sentence? If he was killed that day in September 1977, as I now suspect he was, I hope whatever method they used, my father did not suffer.