Student Union

What Was it Like to be a Chinese Student in 19th Century America?

“This group of boys, dressed in silk gowns, their queues flapping, was too much for New Englanders, be they small-town folk or city dwellers, to ignore. In Springfield, for example, the boys’ dinner at a local hotel was interrupted when an American woman, dining at a nearby table, stood up and wordlessly approached the Chinese youths and started dreamily fondling their queues … They were less amused a few days later when, while visiting Hartford, American children chased them down the street, pushing and shoving each other for a better glimpse of the strange, new breed of humans that had arrived on their shores. … The more fearful among them recalled the horrific stories circulated back home about Americans and their desire to turn the Chinese boys into sideshow curiosities.”

In 1872, when 30 Chinese students arrived on America’s east coast as part of an educational program sponsored by the Chinese government, they attracted quite a bit of attention.

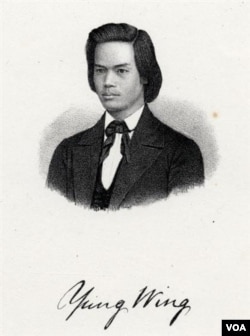

They weren't the first to study in the area though. The first Chinese student ever to receive a degree in the U.S. was Yung Wing, who came to America for high school in 1847 and received his diploma from Yale University in 1852. Yung then spearheaded an educational mission to send 120 Chinese boys to study in the U.S. for 15 years, arriving in dispatches of 30 per year.

What would it have been like to be one of those Chinese students in the 1800s?

Part of the answer can be found in letters and diaries kept by the students, which authors Leil Leibovitz and Matthew Miller used to write a book called Fortunate Sons: The 120 Chinese Boys Who Came to America, Went to School, and Revolutionized an Ancient Civilization.

“We were amazed to find how meticulous these men had been about documenting their lives,” Leibovitz said about writing the book. “So you really just had to open the boxes, which to my amazement and great fortune, no one had thought of doing in the century that passed.”

Yung Wing also published a memoir recounting his experience, as did Li En Fu, one of the 120 to participate in the educational mission.

Here, in their own words, is how Chinese students experienced 19th century America.

How did they apply?

Here’s how students apply today.

Yung Wing wrote in his memoir, My Life in China and America, that he was attending the first English school in China when he got a unique opportunity:

“[Schoolmaster Rev. S.R. Brown] left China in the winter of 1846. Four months before he left, he one day sprang a surprise upon the whole school. He told of his contemplated return to America on account of his health and the health of his family. Before closing his remarks by telling us of his deep interest in the school, he said he would like to take a few of his old pupils home with him to finish their education in the United States … When he requested those who wished to accompany him to the States to signify it by rising, I was the first one on my feet.”

The 120 boys who followed him in 1872 had rather a different experience.

In When I Was a Boy in China Li En Fu recalled, “A school was established at Shanghai to receive candidates, and announcement made that the government had appropriated a large sum or money to educate one hundred and twenty boys in America, who were to be sent in four detachments …”

“… I was taken to the Tung Mim Kuen, or Government School, where I was destined to spend a whole year, preparatory to my American education … It was afternoon, and the Chinese lessons were being recited. … At half-past four o’clock, school was out and the boys, to the number of forty, went forth to play. They ran around, chased each other and wasted their cash on fruits and confections. …

After breakfast the following morning we assembled in the same schoolroom to study our English lessons. The teacher of this branch was a Chinese gentleman who learned his English at Hongkong. The first thing to be done with me was to teach me the alphabet. … It took me two days to learn them. The letter R was the hardest one to pronounce, but I soon learned to give it, with a peculiar roll of the tongue even. … A year thus passed in study and pastime. Sundays were given to us to spend as holidays.

It was in the month of May when we were examined in our English studies and the best thirty were selected to go to America, their proficiency in Chinese, their general deportment and their record also being taken into account.”

According to Ning Qian in his book Chinese Students Encounter America, “The parents of the first group of 30 boys sent to America in 1872 had to sign an agreement to 'accept the will of destiny should the child become ill or die' during the study.”

How did they get there?

Here’s how it’s done today.

In the 1800s, the only way to get from China to America would have been by boat. Yung described his journey like this:

“The tops of the masts and ends of the yards were tipped with balls of electricity. The strong wind was howling and whistling behind us like a host of invisible Furies. The night was pitch dark and the electric balls dancing on the tips of the yards and tops of the masts, back and forth and from side to side like so many infernal lanterns in the black night, presented a spectacle never to be forgotten by me. … We landed in New York on the 12th of April, 1847, after a passage of ninety-eight days of unprecendented fair weather.”

Li arrived by boat to San Francisco, which “impressed my young imagination with its lofty buildings – their solidity and elegance. … But the 'modern conveniences' of gas and running water and electric bells and elevators were what excited wonder and stimulated investigation.”

To get to New England, where he was going to study, he had to take a train – the transcontinental railroad, completed only a few years earlier (and built, ironically, largely by Chinese laborers):

“Nothing occurred on our Eastward journey to mar the enjoyment of our first ride on the steamcars – excepting a train robbery, a consequent smash-up of the engine, and the murder of the engineer. We were quietly looking out of the windows and gazing at the seemingly interminable prairies when the train suddenly bounded backward, then rushed forward a few feet, and, then meeting some resistance, started back again. Then all was confusion and terror. Pistol-shots could be made out above the cries of frightened passengers. Women shrieked and babies cried. Our party, teachers and pupils, jumped from our seats in dismay and looked out through the windows for more light on the subject. What we saw was enough to make our hair stand on end. Two ruffianly men held a revolver in each hand and seemed to be taking aim at us from the short distance of forty feet or thereabouts. Our teachers told us to crouch down for our lives. …

In half an hour the agony and suspense were over. A brakeman rushed through with a lamp in his hand. He told us that the train had been robbed of its gold bricks, by five men, three of whom, dressed like Indians, rifled the baggage car while the others held the passengers at bay; that the engine was hopelessly wrecked, the engineer killed; that the robbers had escaped on horseback with their booty; and that men had been sent to the nearest telegraph station to “wire” for another engine and a supply of workmen. One phase of American civilization was thus indelibly fixed upon our minds.”

When he finally arrived in Springfield, Massachusetts, Li was assigned to a host mother, who “put her arms around me and kissed me. This made the rest of the boys laugh, and perhaps I got rather red in the face ; however, I would say nothing to show my embarrassment. But that was the first kiss I ever had had since my infancy.”

What were their studies like?

Here’s what it’s like today.

When Yung graduated from his American high school, he applied to continue his studies at Yale University. He found the academic requirements there fairly stringent:

“How I got in, I do not know, as I had had only fifteen months of Latin and twelve months of Greek, and ten months of mathematics … But I was convinced I was not sufficiently prepared, as my recitations in the class-room clearly proved. Between the struggle of how to make ends meet financially and how to keep up with the class in my studies, I had a pretty tough time of it. I used to sweat over my studies till twelve o’clock every night the whole Freshman year.”

Yung wrote to a friend, “One has no time to think or analyze except study. There is also great excitement among the students themselves…mental excitement … I enjoy its influence very much.”

The boys who came as part of the educational mission lived with American families during their high school years and, according to Leibovitz and Miller, student Y.T. Woo called his host mother:

“... a strict disciplinarian. When we held our knives and forks too low at meals, she would correct us. When she heard us talking in our rooms in the attic after nine or ten p.m., she would shout from below, ‘Boys, stop talking, it is time to sleep.’”

The students were required to attend classes in Chinese language and culture on top of their normal academics, including during summer holidays. But it wasn’t all work. Leibovitz and Miller quoted an American classmate as saying that “at dances and receptions, the fairest and most sought-out belles invariably gave the swains from the Orient the preference.”

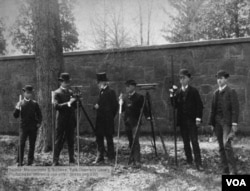

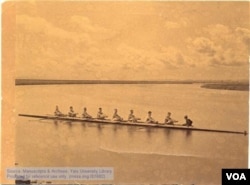

And an American student told this story about classmate Chung Mun Yew’s time as coxswain of Yale’s crew team:

“He was told he must swear at the oarsmen to make them row their best; for he usually sat in his place in silence. Swearing did not come naturally to him, for he was grave and impassive; but finally, being told he must curse them, he would, at the most unexpected moments, and without any emphasis mechanically utter the monosyllable “damn!” whereat the crew became so helpless with laughter, they begged him to desist.” (Leibovitz and Miller)

What was it like when they went home?

Here's what it's like today.

After being in America for over 6 years, Yung experienced some serious culture shock on the way home:

“As we approached Hong Kong, a Chinese pilot boarded us. The captain wanted me to ask him whether there were any dangerous rocks and shoals nearby. I could not for the life of me recall my Chinese in order to interpret for him … So the skipper and Macy, and a few other persons who were present at the time, had the laugh on me, who, being a Chinese, yet was not able to speak the language.”

And, like many modern students, when Yung saw his mother again after so much time away, he had to endure some motherly nagging:

“The interview seemed to give her great comfort and satisfaction. She seemed very happy over it. After it was ended, she looked at me with a significant smile and said, 'I see you have already raised your mustaches. You know you have a brother who is much older than you are; he hasn’t grown his mustaches yet. You must have yours off.' I promptly obeyed her mandate, and as I entered the room with a clean face, she smiled with intense satisfaction, evidently thinking that with all my foreign education, I had not lost my early training of being obedient to my mother.”

The return of Li En Fu and the other boys who participated in the educational mission was a bit different. The politics of the day led to them being recalled to China early, where, upon their arrival, they spent several days in prison on suspicion of being spies.

Books:

Leil Leibovitz and Matthew Miller, Fortunate Sons: The 120 Chinese Boys Who Came to America, Went to School, and Revolutionized an Ancient Civilization

Yung Wing (sometimes written Wing Yung), My Life in China and America

Yan Phou Lee (different spelling for Li En Fu), When I Was a Boy in China

Ning Qian (trans. T.K. Chu), Chinese Students Encounter America

See all News Updates of the Day

- By VOA News

Competition grows for international students eyeing Yale

It’s tough to gain admission to Yale University, and it’s getting even tougher for international students as standout students from around the world set their sights on Yale.

The Yale Dale News, the campus newspaper, takes a look at the situation here.

- By VOA News

Student from Ethiopia says Whitman College culture made it easy to settle in

Ruth Chane, a computer science major from Ethiopia, writes about her experiences settling into student life at Whitman College in the U.S. state of Washington.

"The community at Whitman College made sure I felt welcomed even before I stepped foot on campus," she says.

- By VOA News

Claremont Colleges student gets a shock when she heads home to Shanghai

In The Student Life, the student newspaper for the Claremont Colleges, a consortium of five liberal art colleges and two graduate schools in Claremont, California, student Rochelle Lu writes about readjusting to her Shanghai home after spending a semester in the United States.

- By VOA News

Cedarville University aims to ease transition for international students

Cedarville University in the U.S. state of Ohio says it’s got more than 140 international students representing 44 countries.

Here, the school interviews Jonathan Sutton, director of international student services. He talks about his job and the opportunities for international students on campus.

- By VOA News

Morehouse College offers prospective students tips on applying and thriving

Morehouse College, a private, historically Black liberal arts college in the U.S. state of Georgia, offers a guide for international students interested in attending the school.

Among the tips to apply and thrive at Morehouse:

- Take advantage of the school’s orientation program

- Turn to the school’s Center for Academic Success for tutoring, support and more

- Immerse yourself in campus life via clubs and societies

- By Reuters

US reviews Columbia University contracts, grants over antisemitism allegations

The administration of President Donald Trump said on Monday it will review Columbia University's federal contracts and grants over allegations of antisemitism, which it says the educational institution has shown inaction in tackling.

Rights advocates note rising antisemitism, Islamophobia and anti-Arab bias since U.S. ally Israel's devastating military assault on Gaza began after Palestinian Hamas militants' deadly October 2023 attack.

The Justice Department said a month ago it formed a task force to fight antisemitism. The U.S. Departments of Health and Education and the General Services Administration jointly made the review announcement on Monday.

"The Federal Government's Task Force to Combat Anti-Semitism is considering Stop Work Orders for $51.4 million in contracts between Columbia University and the Federal Government," the joint statement said.

The agencies said no contracting actions had been taken yet.

"The task force will also conduct a comprehensive review of the more than $5 billion in federal grant commitments to Columbia University."

The agencies did not respond to requests for comment on whether there were similar reviews over allegations of Islamophobia and anti-Arab bias.

Columbia had no immediate comment. It previously said it made efforts to tackle antisemitism.

College protests

Trump has signed an executive order to combat antisemitism and pledged to deport non-citizen college students and others who took part in pro-Palestinian protests.

Columbia was at the center of college protests in which demonstrators demanded an end to U.S. support for Israel due to the humanitarian crisis caused by Israel's assault on Gaza. There were allegations of antisemitism and Islamophobia in protests and counter-protests.

During last summer's demonstrations around the country, classes were canceled, some university administrators resigned and student protesters were suspended and arrested.

While the intensity of protests has decreased in recent months, there were some demonstrations last week in New York after the expulsion of two students at Columbia University-affiliated Barnard College and after New York Governor Kathy Hochul ordered the removal of a Palestinian studies job listing at Hunter College.

A third student at Barnard College has since been expelled, this one related to the occupation of the Hamilton Hall building at Columbia last year.

Canada’s immigration overhaul signals global shift in student migration

From Europe to North America, nations are tightening their immigration policies. Now Canada, long seen as one of the world's most welcoming nations, has introduced sweeping changes affecting international students. The reforms highlight a growing global trend toward more restrictive immigration policies. Arzouma Kompaore reports from Calgary.

Trump administration opens antisemitism inquiries at 5 colleges, including Columbia and Berkeley

The Trump administration is opening new investigations into allegations of antisemitism at five U.S. universities including Columbia and the University of California, Berkeley, the Education Department announced Monday.

It's part of President Donald Trump's promise to take a tougher stance against campus antisemitism and deal out harsher penalties than the Biden administration, which settled a flurry of cases with universities in its final weeks. It comes the same day the Justice Department announced a new task force to root out antisemitism on college campuses.

In an order signed last week, Trump called for aggressive action to fight anti-Jewish bias on campuses, including the deportation of foreign students who have participated in pro-Palestinian protests.

Along with Columbia and Berkeley, the department is now investigating the University of Minnesota, Northwestern University and Portland State University. The cases were opened using the department's power to launch its own civil rights reviews, unlike the majority of investigations, which stem from complaints.

Messages seeking comment were left with all five universities.

A statement from the Education Department criticized colleges for tolerating antisemitism after Hamas' Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel and a wave of pro-Palestinian protests that followed. It also criticized the Biden administration for negotiating "toothless" resolutions that failed to hold schools accountable.

"Today, the Department is putting universities, colleges, and K-12 schools on notice: this administration will not tolerate continued institutional indifference to the wellbeing of Jewish students on American campuses," said Craig Trainor, the agency's acting assistant secretary for civil rights.

The department didn't provide details about the inquiries or how it decided which schools are being targeted. Presidents of Columbia and Northwestern were among those called to testify on Capitol Hill last year as Republicans sought accountability for allegations of antisemitism. The hearings contributed to the resignation of multiple university presidents, including Columbia's Minouche Shafik.

An October report from House Republicans accused Columbia of failing to punish pro-Palestinian students who took over a campus building, and it called Northwestern's negotiations with student protesters a "stunning capitulation."

House Republicans applauded the new investigations. Representative Tim Walberg, chair of the Education and Workforce Committee, said he was "glad that we finally have an administration who is taking action to protect Jewish students."

Trump's order also calls for a full review of antisemitism complaints filed with the Education Department since Oct. 7, 2023, including pending and resolved cases from the Biden administration. It encourages the Justice Department to take action to enforce civil rights laws.

Last week's order drew backlash from civil rights groups who said it violated First Amendment rights that protect political speech.

The new task force announced Monday includes the Justice and Education departments along with Health and Human Services.

"The Department takes seriously our responsibility to eradicate this hatred wherever it is found," said Leo Terrell, assistant attorney general for civil rights. "The Task Force to Combat Anti-Semitism is the first step in giving life to President Trump's renewed commitment to ending anti-Semitism in our schools."

- By VOA News

STEM, business top subjects for international students

The Times of India breaks down the most popular subjects for international students to study in the U.S.

STEM and business lead the pack. Read the full story here. (January 2025)

- By VOA News

Safety and visa difficulties among misconceptions about US colleges

U.S. News & World report addresses some of the misconceptions about U.S. colleges and universities, including the difficulty of getting a visa.

Read the full story here. (January 2025)

- By VOA News

Work opportunities help draw international students to US schools

US News & World Report details the three top factors in foreign students' decision to study in the U.S. They include research opportunities and the reputation of U.S. degrees. Read the full story here. (December 2024)

- By VOA News

British student talks about her culture shock in Ohio

A British student who did a year abroad at Bowling Green State University in Ohio talks about adjusting to life in America in a TikTok video, Newsweek magazine reports.

Among the biggest surprises? Portion sizes, jaywalking laws and dorm room beds.

Read the full story here. (December 2024)

- By VOA News

Harvard's Chan School tells international students what to expect

Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health reaches out to international students by detailing the international student experience at the school.

Learn more about housing, life in Boston and more here.

- By Reuters

China unveils plan to build 'strong education nation' by 2035

China issued its first national action plan to build a "strong education nation" by 2035, which it said would help coordinate its education development, improve efficiencies in innovation and build a "strong country."

The plan, issued Sunday by the Communist Party's central committee and the State Council, aims to establish a "high quality education system" with accessibility and quality "among the best in the world."

The announcement was made after data on Friday showed China's population fell for a third consecutive year in 2024, with the number of deaths outpacing a slight increase in births, and experts cautioning that the downturn will worsen in the coming years.

High childcare and education costs have been a key factor for many young Chinese opting out of having children, at a time when many face uncertainty over their job prospects amid sluggish economic growth.

"By 2035, an education power will be built," the official Xinhua news agency said, adding that China would explore gradually expanding the scope of free education, increase "high-quality" undergraduate enrolment, expand postgraduate education, and raise the proportion of doctoral students.

The plan aims to promote "healthy growth and all-round development of students," making sure primary and secondary school students have at least two hours of physical activity daily, to effectively control the myopia, or nearsightedness, and obesity rates.

"Popularizing" mental health education and establishing a national student mental health monitoring and early warning system would also be implemented, it said.

It also aims to narrow the gap between urban and rural areas to improve the operating conditions of small-scale rural schools and improve the care system for children with disabilities and those belonging to agricultural migrant populations.

The plan also aims to steadily increase the supply of kindergarten places and the accessibility of preschool education.

- By VOA News

A look at financial aid options for international graduate students in US

The Open Notebook, a site focusing on educating journalists who cover science, has complied a list of U.S. graduate program financial aid information for international students.