Ruksana Begum and her classmates repeat after their teacher: “respect.”

The students are all Rohingya refugees who fled to Bangladesh from neighboring Myanmar. Nine-year-old Ruksana says she hopes to become a teacher herself one day. But her current instructor, as hard as he tries, is not really qualified for the job.

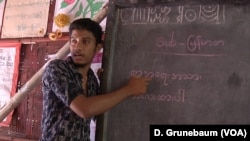

Shamsuddin, a 21-year-old Rohingya refugee himself, says he has only completed high school, which is a common situation for many of the teachers in the refugee camps.

“We are quite well aware that these teachers don’t have the competencies and the skills to really teach,” says Jean Metenier of UNICEF, adding that there is ongoing training to improve the skills of the instructors.

Too few classrooms, teachers

The unqualified teachers are just one of the problems when it comes to educating the child refugees, which also include too little classroom time and not enough classrooms.

More than 700,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled from Myanmar’s Rakhine State to neighboring Bangladesh since a military crackdown in August 2017. United Nations investigators have said the operation was conducted with “genocidal intent.” Myanmar denies the accusations and says its security forces ran a legitimate counterterrorism campaign after attacks by Rohingya militants.

WATCH: Aid Groups Face Challenges in Educating Rohinyga Children

The refugees now live in overcrowded camps. The sudden surge in school-age kids has prompted aid groups to build classrooms, develop a curriculum and give crash courses in teaching to teams of inexperienced instructors.

Most classrooms have two teachers. One is Rohingya and gives lessons on Myanmar language also known as Burmese and life skills. The other instructor is from Bangladesh and typically teaches English and math. The Bangladeshi instructors often speak the local Chittagonian dialect, which has a lot of overlap with the Rohingya language.

The refugees are not allowed to enroll in Bangladesh schools, so UNICEF and non-governmental organizations have built about 2,000 of what they call “learning centers” in the camps for students ages 4 to 14.

Incremental approach

They plan to have another 500 running by the end of the year. Currently about one-third of the 300,000 child refugees in that age range do not have access to a learning center. UNICEF says the reasons include issues with fundraising as well as the time it takes to hire and train teachers. Most children who are enrolled are only in class for two hours a day.

Metenier acknowledges that is not enough to provide an adequate education, but says it’s enough time to give the children a basic education where they can develop a foundation in literacy and numeracy along with life skills.

Administrators say they’re taking an incremental approach in the refugee camps.

“We started from almost nothing,” said Beatriz Ochoa of Save The Children. “Building little by little: The capacities of the teachers, building the temporary learning centers, building a curricula.”

However, there’s another issue educators here have inherited from Myanmar, where the Rohingya face limitations on access to school. Assessment tests show that 65 percent of the refugees ages 4 to 14 have not reached the academic level of a first grader.

Parents worry

“We can not see any good future for our children if they don’t get the proper education they need,” says Mohammed Hares, the father of Ruksana Begum.

Plus, because of limited funds and younger kids being prioritized, few youth older than 14 currently have any educational opportunities in the camps. UNICEF’s Metenier says that will start changing this year as vocational training programs are developed and an accelerated basic education curriculum is added for older youth who need to learn basic arithmetic and literacy.

“A big priority will be the focus which we’re going to put on the adolescents,” Metenier said. “Giving them some skills they can use for their future.”