In August 1968, Soviet tanks stormed into then communist-ruled Czechoslovakia — abruptly ending attempts by the government in Prague to build a more just society under the slogan “socialism with a human face.”

While the Soviet government assured its citizens the troops were there to provide “friendly assistance,” the invasion was met with despair among Russian pro-democracy activists. In the Kremlin’s crackdown on the ‘Prague Spring,’ many saw a harbinger for further repression at home.

“There was a hope that Czechoslovakia will start some reforms and these reforms will help not only Czechoslovakia but us in Russia, if they will stick,” says Pavel Litvinov, a former Soviet dissident who would come to play a pivotal role in the events to follow.

A 28-year-old physicist at the time, Litvinov secretly planned with seven other dissidents to carry out a public protest on Red Square in support of their Czech and Slovak comrades.

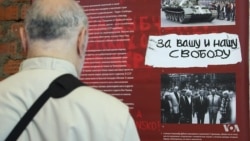

As the Kremlin clocks chimed noon, they sat and unfurled a banner that simply read: “For Your Freedom and Ours.” Another member of the group, the poet Natalya Gorbunovskaya, held a Czechoslovakian flag to drive the message home.

The demonstration lasted just minutes before KGB agents charged in. Litvinov recalls being hit over the head with what he assumes was a bag of books or bricks. “Maybe it was volumes of Karl Marx?” jokes Litvinov, while recalling the event in an interview with VOA.

The banner and flag were ripped from their hands. Another of the eight, Victor Feinberg, was struck in the face with brass knuckles, revenge for tripping up a KGB officer. His front teeth dropped into his hands.

Labor camp punishment

The more lasting punishment would come later.

“There was no question. I expected seven years of labor camp like many of my friends for so-called ‘anti-Soviet propaganda,'” says Litvinov.

Instead, he was sentenced to five years exile in a Siberian mining camp.

Others had similar fates — or were punished by other means. Gorbunovskaya and Feinberg were committed to Soviet psychiatric wards and force treated for schizophrenia. Upon release, all eventually emigrated abroad under threat of further harassment. Litvinov emigrated to the U.S. in 1974, eventually taking citizenship.

The Red Square protest was hardly the first act of defiance against the Soviet authorities but the event was nonetheless a defining moment a dissident movement settling in for the long struggle ahead.

“The demonstration of the 25th of August in the Red Square was a model,” says Alexander Daniel, a historian of the Soviet human rights movement. After August 1968, notes Daniel, the protesters showed how to act when there was “no hope of practical results or improving the situation. It became clear that we were at the start of a very long epoch.”

“It wasn’t for nothing that people went to prison or were exiled,” counters Ksenia Sakharnova, a filmmaker whose 2010 documentary “Five Minutes of Freedom” recalls the 1968 protest. “Because it wasn’t simply a one-off demonstration that everyone soon forgot about. It resonated widely…and it’s an example to today’s young activists.”

Yet polls today show under half of all Russians — just 46 percent, according to the independent Levada Center — are unaware of the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. Fewer still of the Red Square protest it inspired.

'Managed democracy'

Meanwhile, state pressure against opposition figures and government critics remains a regular feature of President Vladimir Putin’s system of so-called “managed democracy.”

Indeed, in the Kremlin’s current proxy war in Ukraine and general rollback on political freedoms at home, family members of the Red Square demonstrators say they see parallels with 1968.

“If then it was a story about how Czechoslovakia had freedoms and lost it under the tanks, today it’s a story about how Russians gained freedom and then lost it… or are losing it,” says Yaroslav Gorbanevsky, the son of Natalya Gorbanevskaya, who died in 2013.

“And again there are tanks — only not on Red Square, they’re now in Ukraine and in Crimea.”

50th anniversary

Gorbonevsky was on Red Square to join Litvinov and other descendants of the 1968 demonstrators — most have since passed away — to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the event.

Yet history wasn’t on their minds for long.

Almost unnoticeable against a backdrop of tourists, Litvinov — now 78 — addressed a small crowd and called for the release of current day political prisoners as the Kremlin clock struck noon.

Only soon Serge Sharov-Delaunay, the cousin of 1968 protester Vadim Delaunay (1947-1983) was arrested while trying to display a “For Your Freedom and Ours” banner with a friend.

Minutes later, Nusya Krasovitskaya, the granddaughter of the poet Gorbunovskaya, was escorted away by officers. Her crime? Expressing support for Oleg Sentsov, a jailed Ukrainian filmmaker currently engaged in a 3-month hunger strike over his opposition to Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Meanwhile, in a separate event across town, Russia’s current opposition leader — the anti-corruption crusader Alexey Navalny — was detained outside his apartment amid calls for demonstrations against reforms to Russia’s pension system.

All, with the exception of Navalny, were released within hours.

But the message was clear: 50 years after a small Red Square protest inspired generations of civil and political disobedience, it is still limits, rather than freedoms, that define the times.